On February 14, 2014 in the case of Nairobi Pacific Hotel vs KAMP & PRISK CMCC 7240 of 2013, the court dismissed an application filed by Nairobi Pacific Hotel seeking a grant of temporary injunction to restrain the Kenya Association of Music Producers (KAMP) and the Performers Rights Society of Kenya (PRiSK) from collecting fees with respect to their jointly-issued Communication to the Public license. A copy of the ruling is available here.

This court ruling creates an important precedent that a Public Performance License from the Music Copyright Society of Kenya (MCSK) is not sufficient for the protection of the rights of performers and producers represented by PRiSK and KAMP, respectively. In making its ruling, the court noted that KAMP and PRiSK are collective management organisations (CMOs) duly licensed by the Kenya Copyright Board (KECOBO) to collect license fees from the users who broadcast or communicate sound recordings and audiovisual works to the public.

The court further finds that the clean hands doctrine applies since the user in question, Nairobi Pacific Hotel, had been implored upon to obtain a Communication to the Public License but neglected and/or refused to do so solely on the basis that the latter had already obtained a Public Performance License from MCSK.

Comment:

This blogger supports the court’s ruling in this matter and applauds the related rights CMOs for successfully using litigation as a tool to enforce and protect the rights of their respective members.

The existence of the MCSK license and KAMP-PRiSK for public performance is premised on the definition of the “communication to the public” in the Copyright Act. This definition reads:

“communication to the public” means

(a) a live performance; or

(b) a transmission to the public, other than a broadcast, of the images or sounds or both, of a work, performance or sound recording;”

However the Copyright Regulations of 2004 provide the clearest definition of what amounts to “Public Performance” as it is licensed by MCSK for the rights under copyright and KAMP-PRiSK for the related rights.

Section 2 reads as follows:

“public performance” means –

(a) in the case of a work other than an audio-visual work, the recitation, playing, dancing, acting or otherwise performing the work, either directly or by means of any device or process;

(b) in the case of an audio-visual work, the showing of images in sequence and the making of accompanying sounds audible; and

(c) in the case of a sound recording, making the recorded sounds audible at a place or at places where persons outside the normal circle of the family and its closest acquaintances are or can be present, irrespective of whether they are or can be present at the same place and time, or at different places or times, and where the performance can be perceived without the need for communication to the public.

From the users’ perspective, they argue that public performance licensing by KAMP – PRiSK and MCSK “feels like double taxation since one is paying 3 different bodies licence fees for the same thing”. Herein lies the biggest challenge for CMOs: to successfully convince users that “music”, as they know it, is simultaneously categorised as three different subject matter under copyright law, namely “sound recordings”, “musical works” and “audio-visual works”. In this regard, this blogger has previously argued here that it requires a great deal of skill and salesmanship for licensing officers from the CMOs to convince users to take out their respective licenses.

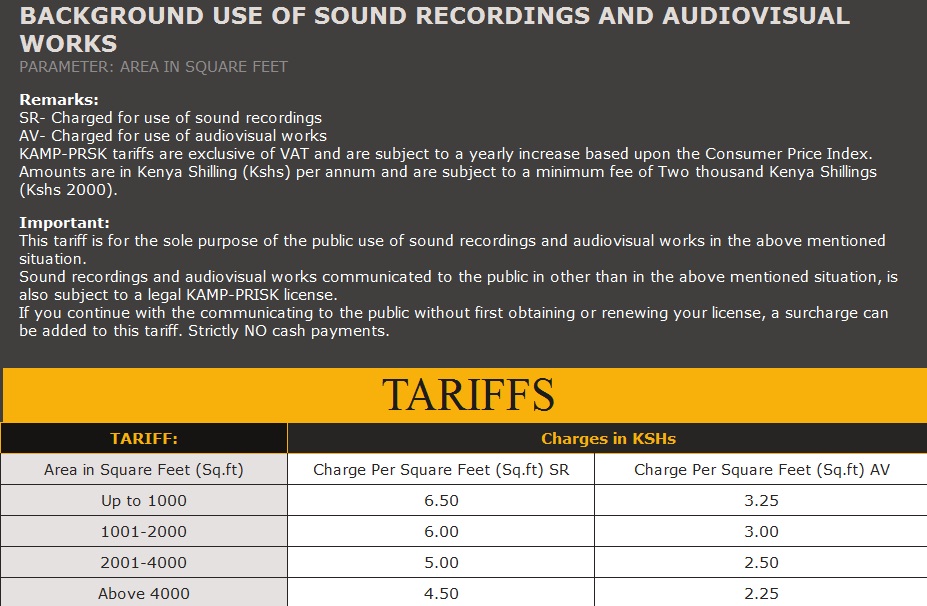

In the present case of the KAMP-PRiSK license, the tariffs are based on the area in square feet of the business premises wwhere the sound recordings and audio-visual works are used. The tariff structure is available below:

In disputes between CMOs and users, the elephant in the room always seems to be the question of CMO regulation, in particular the reasonableness of the license terms and conditions imposed by CMOs on users. As previously discussed here and here, this blogger has noted that there is an increase in complaints by users against CMOs relating to license fees, in addition to the manner in which license fees are collected from users.

In the case of KAMP and PRiSK, CMO-user relations appear to have been complicated further with the enactment of section 30A in the 2012 Amendments to the Copyright Act. It would seem that Section 30A has introduced a system of compulsory licensing with the introduction of the right to equitable remuneration for use of sound recordings and audio- visual works. However, the term “equitable remuneration” remains undefined and where users of sound recordings and audio- visual works may have complaints against KAMP and PRiSK, the Competent Authority is not yet in operation to give directions on these matters.