By Mercy Mutemi**

The world over, copyright owners have resigned to the reality that is it is now harder to protect their copyright over the internet in the age of the BitTorrent network, indexing sites and streaming sites. Indeed legislation is in place recognizing and protecting the economic and moral rights of authors, yet enforcing such protection remains elusive. It is no wonder then that countries are looking to ISPs to uphold copyright protection given the key role they play in availability of content. Kenya has not been left behind- the recently published Copyright (Amendment) Bill, 2017 is set to co-opt ISPs in the fight against piracy.

The Bill is available online here.

To begin with, the Bill is categorical that ISPs will neither have an obligation to monitor content nor to investigate infringing activity within its services.

Notice-and-Takedown Procedure

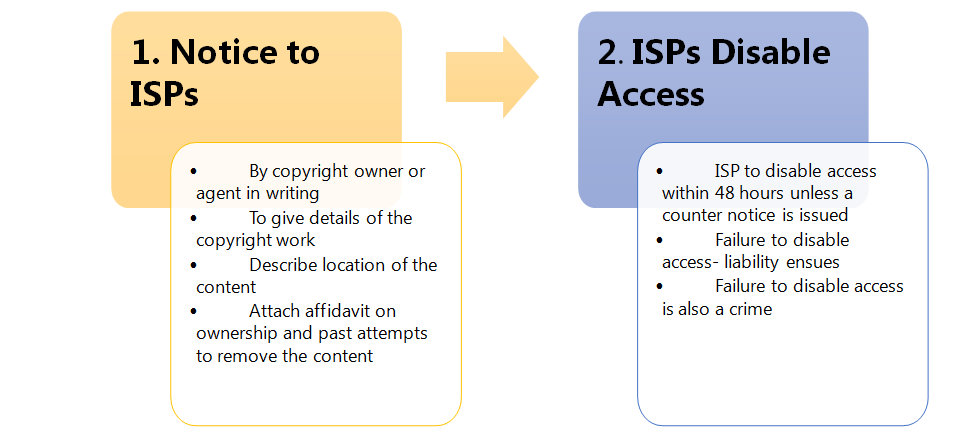

The Bill proposes a two-step notice-and-takedown procedure for ISPs to disable access to allegedly infringing material. This procedure is problematic for a couple of reasons.

One, this turns the ISPs into arbiters. They are to consider requests from persons claiming to be copyright owners and peruse the affidavits on ownership and on the attempts made to contact the websites hosting the infringing material. The impugned websites will have the right to file counter notices with the ISPs. The Bill is however silent on what the ISP is to do in case a counter notice is filed.

Secondly, the Bill does not anticipate competing claims. It is therefore possible for an ISP to be dragged into copyright ownership and infringement disputes. This is especially so because of the provision on enforcement that requires compliance with a takedown notice, malicious or not, within 48 hours. Making it an offence not to do so, while intended to secure compliance, reignites the debate on corporate criminal responsibility in light of Section 23 of the Penal Code.

Other countries have an intermediate step between notice by the copyright owner and action by the ISP. Australia requires the copyright owners to obtain an injunction order from the Federal Court. It is the Court that will instruct the ISPs to disable access to infringing content. It is also the Court that will make a finding on whether or not the applicant has a bona fide claim as the copyright owner. For more on how effective shifting the focus to ISPs has been for Australia please click here.

Italy introduced the AGCOM procedure in 2013 where AGCOM (an administrative body) may accept submissions from right holders and issue orders requiring ISPs to block infringing websites without court intervention. This includes a fast track procedure with a 12-day turnaround. India allows copyright holders to complain to the ISP of infringement after which the ISP is to block access for a period of twenty one days. If the complainant does not obtain a court order before the lapse of the 21 days, the ISP is free to continue providing access.

Having an intermediate body consider these cases before directing an ISP to block access to a website safeguards due process and minimizes the chances for ill-conceived applications. Copyright disputes are not straightforward. Similarly, not all infringement of copyright is actionable- there are instances where liability is excused e.g. for educational purposes. An ISP following through with a notice in these instances would be exposed to consumer fall out. Fundamental questions such as what amounts to infringement are difficult even for the courts. It is therefore untenable to leave these concerns to play out as between a copyright owner and an ISP especially where the law forces the ISP to effect a block or be exposed to liability.

Another concern is that the Bill does not seem to address the issue of who pays the cost of website blocking. ISPs are not the wrongdoers even when their networks are used to infringe copyright. Furthermore, infringements via torrent sites feature numerous secondary websites that automatically re-direct to the primary website. To effectively put an end to such an infringement, an ISP would have to block access to each and every one of the secondary website as well as the primary website. This is a cost to business which cumulatively would be punitive. A balance must be struck between the ISPs right to carry on business versus the owners right to have their copyright protected.

‘Safe Harbours’

The Bill introduces the Kenyan version of ‘safe harbours’. Borrowed from the American legal framework, safe harbours constitute conduct by ISPs that is exempt from liability.

The first of these is where an ISP provides access to, transmits, routes or provides storage for infringing content in the ordinary course of business. Secondly, an ISP will be exempt from liability for infringement in cases of automatic, intermediate and temporary storage of infringing content for efficient transmission (system caching). The third exemption is where infringing content is stored at the request of the recipient and the fourth exemption covers instances where the ISP refers users to a webpage containing infringing content. These exemptions subsists as long as the ISPs comply with a set of exemptions outlined under each.

This is a welcome development. The exemptions represent aspects of the normal operation of the internet that must be protected even as we seek to enhance copyright protection.

Good or Bad?

While the inclusion of the safe harbour exemptions is welcome, it is doubtful that including ISPs in the fight against copyright infringement will be successful. If persistent trends are anything to go by, co-opting ISPs is likely to have little or no effect on copyright infringement online. Piracy sites have cultic followings; bringing down one site gives impetus to create ten more. The copyright owner must be willing to invest the time in researching all other pop-up sites and issuing notices perhaps on a daily basis. In cases where the Courts have given takedown orders, parties find themselves going back to court after a few months for similar orders. Unfortunately copyright owners would have to independently issue takedown notices to all the ISPs unlike in the case of an application to court where all the ISPs become co-respondents. The takedown procedure is more likely to be a business nuisance for both parties than an effective way of protecting copyright.

As we speak, the Copyright (Amendment) Bill 2017 has already gone through the First Reading in the National Assembly. For any submissions on the Bill, please use the following contact:

Mr. Michael Rotich Sialai, EBS

The Clerk, Kenya National Assembly,

Parliament Buildings,

P.O Box 41842-00100

NAIROBI

clerk@parliament.go.ke

We would love to hear from readers of this blog on the Bill and its proposed provisions. Please let us know what you think via the comments box below or via social media.

**Mercy Mutemi is an Advocate of the High Court of Kenya. Follow her on twitter at: @MercyMutemi