#DigitalMigration Update: Post-Advert Action and Lingering Copyright Issues

- Victor Nzomo |

- February 4, 2015 |

- CIPIT Insights

In the January 2015 update on #DigitalMigration, we focused on a controversial television (TV) infomercial by Royal Media Services (RMS), Nation Media Group (NMG) and Standard Group (SG) on their respective TV channels in which they alleged that GOTv and StarTimes were broadcasting the former’s TV channels without consent thereby infringing on the copyright and related rights of RMS, NMG and SG. The advert went further to advise members of the public not to purchase GOTv and StarTimes set top boxes until RMS, NMG and SG launch their own set top boxes. This advert came in the wake of an order by two judges of the Supreme Court on January 5, 2015 temporarily blocking the Communications Authority of Kenya from switching off the analogue signals of the three media houses after the latter made an urgent application requesting more time to complete the migration from analogue to digital broadcasting.

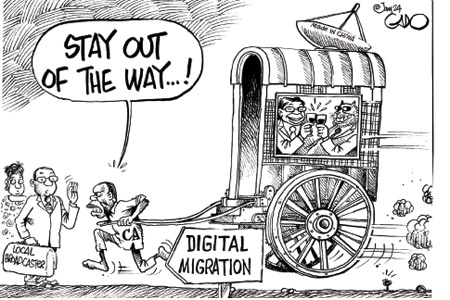

This month, there have been several developments in the on-going #digitalmigration saga all stemming from the Supreme Court’s controversial decision that the so-called “must-carry rule” under the Kenya Information and Communications Act (KICA) does not amount to an infringement of copyright and related rights of works belonging to RMS, NMG and SG.

Shortly after GOtv and StarTimes successfully obtain court orders to stop the airing of the informercial, the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) took stern action against RMS, NMG and SG in two ways: first, CA withdrew the temporary authorization granted to facilitate the roll out their digital signal distribution platform (self-provisioning signal distribution infrastructure). Second, CA fined the three media houses Kshs 500,000.00 each for breaching broadcasting regulations. In addition to the fine, CA ordered the three media houses to commit to carry advertisements on digital migration and not to use their channels to carry selective and misleading information; and not to engage in anti-competitive behaviour; and to comply with the type approval procedures. The CA gave the media houses seven (7) calendar days, effective February 6, 2015, to adhere to the conditions and CA would lift its suspension and resume the processing of the self-provisioning licence for the three media houses.

Several legal commentators have come out strongly to condemn CA’s actions as well as the underlying Supreme Court decision on the copyright dimension of digital migration. Hezekiel Oira, former General Counsel and Company Secretary at the national broadcaster Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) has penned two articles on this subject publishing in the Standard and Nation newspapers available here and here respectively. In his Standard article titled “Communications Authority’s interference with media ill-advised”, Oira deconstructs the concept of a “must carry rule” and demonstrates its problematic existence vis-a-vis KICA, the Copyright Act and the Constitution of Kenya. Oira makes the following poignant remarks:

The [must carry] rule, being a subsidiary legislation, falls foul of the Constitution, Parent legislation, Copyright Act and relevant international instruments. First, section 46 of the Kenya Information and Communications Act enjoins all licensed broadcasters to respect copyright and neighbouring rights. This provision is in conflict with rule 14(2) that gives the authority apparent power to cause licensees to violate the same copyright law.

Article 40(5) of the Constitution enjoins the state to support, promote and protect the intellectual property rights of its people, including those of the three media houses. The CA’s act therefore undermined the constitutional protection of the three organisations. The state has a constitutional duty to ensure that constitutionality prevails in this matter.

Copyright law gives broadcasters a monopoly right of excludability over their broadcasts subject to the prescribed exceptions and limitations. Looking at the advertisements which were placed by the three media houses, they were in accord with the Constitution, Kenya Information and Communications Act, Copyright Act, and Rome Convention.

In his Nation article titled “Using ‘must carry’ cloak to violate TV firms’ copyright”, Oira, a former KECOBO Board Member, re-states his position in the Standard article on the inconsistencies between the “must carry” rule and copyright law in Kenya.

In this regard, Oira notes that:

S.29 of the Copyright Act provides that copyright in a broadcast shall be the exclusive right to control the doing in Kenya of any of the following acts: “fixation and rebroadcasting of the whole or substantial part of the broadcast…”

The Copyright Act finds legal backing in the Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organisations, of which Kenya is a signatory directly or by extension through the TRIPs Agreement of 1994.

Article 13 of the Rome Convention obliges Kenya to grant broadcasting organisations exclusive right to authorise or prohibit: Rebroadcasting of their signals; Fixation of their broadcasts; The reproduction:

a) of fixations made without their consent; b) of fixations made for unauthorised purposes; Communication to the public of their TV broadcasts against payment of entrance fee.

The media houses had a right to claim ownership of their broadcasts as well as make it plain that they had not authorised their rebroadcasting, reproduction or retransmission. Such unauthorised retransmissions could also cause secondary infringement of copyright where content is acquired on the basis of platforms of delivery.

Oira concludes his article by differing with the Supreme Court decision which found that “rebroadcasting” under the must-carry rule falls within “fair dealing” under the Copyright Act. In this regard, he states as follows:

The Copyright Law in Kenya has provided a repertoire of exceptions and limitations under which copyrighted works may be used without the consent of the owner. The one cited in the dispute is fair dealing. S.26(1) of the Copyright Act, however, restricts fair dealing to scientific research, private use, criticism or review or the reporting of current events subject to acknowledgement of the source.

The “must carry” rule does not fit into this particular exception and limitation.

At the same time, prominent legal scholar Wachira Maina has belatedly weighed in on the “confusion” created by the Supreme Court in the “muddling” of copyright law in an article available here.

Maina’s argument is thus:

The real issue, though, is that CA has a fundamental misunderstanding of the ‘must-carry’ rule as implemented in other jurisdictions. And the authority’s confusion has been given legs by a Supreme Court decision that got all mixed up about the copyright exception called ‘fair dealing’ and the broadcasting rule called ‘must carry.’

There are three points to make: First, both CA and the Supreme Court are wrong on the ‘must-carry’ rule. Second, the Supreme Court is wrong in treating the ‘must-carry’ rule (a broadcasting matter) and fair dealing (a copyright exception) as mutually inclusive. Third, the Supreme Court was wrong in using subsidiary legislation to limit property rights granted by the Constitution, including intellectual property rights.

The confusion wrought by the authority and fortified by the Supreme Court arises from a failure to distinguish the nature of the broadcasting market and the public interest issues at stake in its regulation.

The #DigitalMigration story took a bizarre turn this month when the three media houses represented by Senior Counsel Paul Muite claimed that they would seek international intervention to address what they considered as contravention of international intellectual property laws and bias by the Government (both the Executive and Judicial branches). Many IP commentators were left wondering: “Is that even possible?” “Which international IP forum/court/tribunal is this? See for yourselves:

The #DigitalMigration saga continues…