by Wiseman Qinani Ngubo

This past week we have seen many different opinions on various platforms on the jury decision to award the Gaye family $7.3 million in the Blurred Lines case. The Gaye family have not only taken a substantial amount of money from Pharrell & Robin Thicke they have also in turn prejudiced the general public by effectively privatising what was in and what should remain in the public domain.

What is the public domain in the context of intellectual property law? The public domain is sometimes referred to as “the commons” and comprises works that are not protected by intellectual property law, works that have lost the limited protection initially granted and fallen back into the public domain as well as aspects of intellectual property where permission is not required such as ideas or fair use/experimental exceptions etc. It is essentially any and all things that are freely available to the general public in respect of all intellectual property.

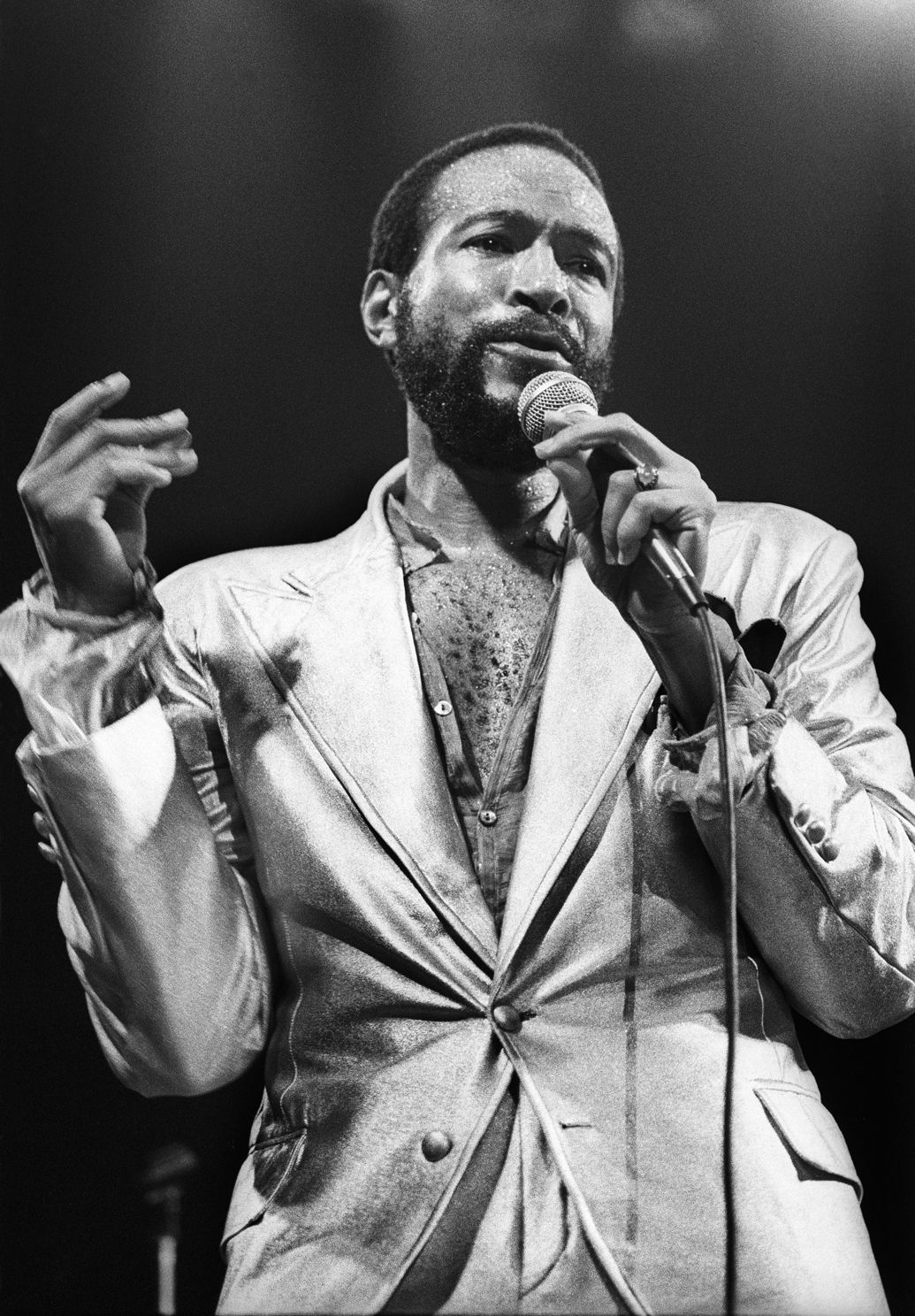

The case was based on what is said to the “feel” of Blurred Lines being similar to Marvin’s Got To Give It Up. Robin & Pharrell had been quoted as saying they had attempted to invoke an era and had drawn inspiration from the song but had not in fact used any of its elements.

The appreciation of the basic premise of copyright law itself was unfortunately lost to the jury. Copyright (like all intellectual property law) at its core, is not about extending or perpetually protecting private rights but rather, it is about protecting the public domain. The fundamental purpose is to ensure that there is enough material commonly available in order to facilitate and aid further innovation. This is done by granting a limited monopoly as an incentive to creators. The ultimate goal however, is to promote free access and to ensure that the public domain grows. This distinction was best articulated by Thomas Macaulay in his speech to the House of Commons the 19th Century where he averred:

“It is good that authors should be remunerated; and the least exceptionable way of remunerating them is by a monopoly. Yet monopoly is an evil. For the sake of the good we must submit to the evil; but the evil ought not to last a day longer than is necessary for the purpose of securing the good”

We cannot extend monopoly protection to things that should be or which are already in the public domain. In doing we, effectively decrease what is available for the public to use as inspiration for further innovation.

Musicians and indeed Marvin Gaye himself, like all creatives, draw inspiration from the public domain. Granting monopoly for the “feel” of the song is tantamount to copyright protecting an idea in its non-material form. This is against natural law and indeed Copyright law itself which requires the idea to first be reduced to material form before it can be protected. Thomas Jefferson expresses this as follows:

“If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.”

“Feel” is how genres are born. It is unfathomable that one could have copyright protection for the “feel” of all reggae music. In the same breath, how would genres like Techno, EDM, House, Afro-Beats etc be if an individual was granted a monopoly to the “feel” of such genres? This concept is so public that it is pre-programmed into music software and digital instruments like pianos and drumkits. We cannot punish creators for having a muse nor can we extend monopoly protection to those who inspire others. The departure point when dealing with copyright is to understand that ideally, everything should be available to the public. Those who seek monopoly should bear the burden of proof and not the other way around.

The Gaye family and indeed this whole case showcases the dangers of granting copyright monopolies that the early scholars where weary off. Macaulay (quoted in James Boyle’s “The Public Domain: Enclosing The Commons of the Mind”) warned that:

“those who controlled the monopoly, particularly after the death of the original author, might be given too great a control over our collective culture. Censorious heirs or purchasers of the copyright might prevent the reprinting of a great work because they disagreed with its morals”

This case has proven Macaulay’s words true even after 2 centuries of them being uttered. The dangers of the abuse of the copyright monopoly that were apparent then, are manifesting today. The Gaye family has effectively taken what should be commonly available (and indeed that which was available to Marvin Gaye himself when he created the song) and placed it in the private realm for their exclusive use. This is not just a loss for Pharell & Robin Thicke but rather a loss for the music industry, the creative industry as well as the general public as a whole.