This semester, we kick off a brand new course for final year undergraduate law students on e-commerce and the law. This course aims at explaining the legal challenges that are posed by electronic commerce. We shall also contextualise and problematise on-going legal/policy developments in Kenya to regulate electronic commerce. In this blogpost, we explore the implications of taxation. Take for instance the case of Karura, our fictional Kenyan answer to Amazon, an established e-commerce business, with dozens of online platforms. It offers a variety of goods and services to its customers worldwide. Delivery of goods and services takes place on the Internet and payments for purchases are made electronically. Karura is incorporated in Mauritius and has a presence throughout East Africa. Their management board sits in South Africa and decisions are often taken in the United Kingdom. If Kenya wishes to assert the authority to tax Karura in Kenya, is there a basis for exercising such taxing jurisdiction?

A government’s authority is based on territory and jurisdiction. Kenya operates as a territorial tax system – all income derived in Kenya is taxed in Kenya except in situations where exemptions are allowed under Double Tax Agreements (DTA). There is a legitimate concern by governments that the development of the Internet may have the effect of shrinking the tax base and hence reducing fiscal revenue. The Constitution states in Article 201 (b) that the public finance system shall promote an equitable society, and in particular— (i) the burden of taxation shall be shared fairly

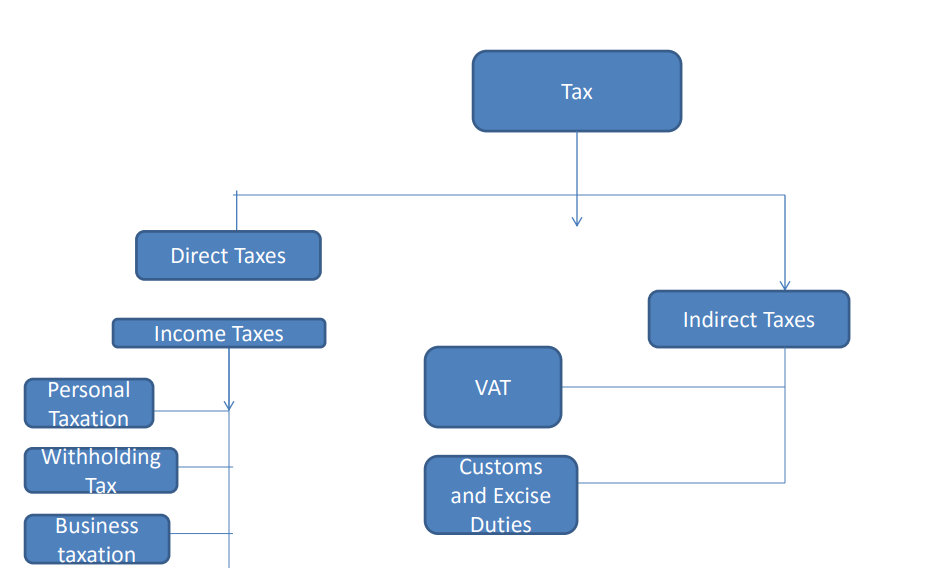

(1) Only the national government may impose—

(a) income tax;

(b) value-added tax;

(c) customs duties and other duties on import and export goods; and

(d) excise tax.

(2) An Act of Parliament may authorise the national government to impose any other tax or duty (…)

It is submitted that Article 201(2) provides ample support for any legislative efforts to appropriately develop tax law in the context of e-commerce in Kenya. It is noted that the evolution of e-commerce raises issues with regard to the application of traditional tax rules to e-commerce. Conventional tax enforcement rules have largely been residence or source based but the application of these rules becomes problematic when dealing with e-commerce. The physical presence and physical delivery of goods or services is largely irrelevant when dealing with digitalized goods or services.

Before any country can levy a tax on income, a connection or tax nexus must be established between itself and that income. The two main connecting factors (principles) underlying the taxation of income are the residence and the source principles of taxation:

Source principle: persons (natural and juristic) are taxed on income that originates within the territorial jurisdiction or geographical confines of the country, regardless of the taxpayer’s country of residence.

Residence principle: residents are taxed on their worldwide income regardless of the fact that the income may have its source from another country.

E-commerce poses challenges to the above principles upon which countries’ jurisdiction to tax income is based. This is because these principles are governed by national sovereignty, having been developed in the days of `bricks and mortar’ when physical presence in a jurisdiction was necessary to enforce tax laws and where cross-border transactions involved mostly tangible products.

The Income Tax Act sets out the residence principle for natural persons as follows:

“resident”, when applied in relation – (a) to an individual means –

(i)that he has a permanent home in Kenya and was present in Kenya for any period in a particular year of income under consideration; or

(ii) that he has no permanent home in Kenya but –

(A)was present in Kenya for a period or periods amounting in the aggregate to 183 days or more in that year of income; or

(B) was present in Kenya in that year of income and in each of the two preceding years of income for periods averaging more than 122 days in each year of income;

This raises the question: can technology make it possible for a person’s mode of life to be such that it cannot be said that he or she has a permanent home anywhere? The answer appears to be no. An individual’s Internet activities are carried out on a computer, inside a building that is in a physical location. It can thus be concluded that cyberspace “presence” should have no effect on a country’s jurisdiction to tax an individual who is ordinarily resident in that country. Likewise, adopting the lifestyle of a permanent wanderer with no intention to be ordinarily resident in one specific country should have no major effect on a country’s jurisdiction to tax an individual who is ordinarily resident in that country. Adopting such a lifestyle would be too extreme a measure for most people, as it would imply that they would not have a home to return to from their wanderings, cannot form and maintain meaningful relationships, accumulate personal belongings or maintain a place of business in a specific location. It has been suggested that it is possible for an individual to avoid numerical residence rules based on periods of physical presence by absenting himself from a given jurisdiction for the necessary number of days while continuing to work for the same employer in an uninterrupted fashion through telecommunications. Although theoretically possible, this lifestyle would be difficult to maintain if its only purpose was tax avoidance, and it will probably rarely be encountered in practice.

The Income Tax Act sets out the residence principle for juristic persons as follows:

“resident”, when applied in relation – (b) to a body of persons, means –

(i) that the body is a company incorporated under a law of Kenya; or

(ii) that the management and control of the affairs of the body was exercised in Kenya in a particular year of income under consideration; or

(iii) that the body has been declared by the Minister by notice in the Gazette to be resident in Kenya for any year of income;

In order to avoid high taxes, a company’s place of incorporation, establishment or formation can be easily relocated to a low tax jurisdiction. However the question remains how does one define the location where “the management and control of the affairs of the body was exercised”? Article 4(3) of the OECD Model Tax Convention proposes that “the taxing power is accorded to the state in which the place of effective management of the entity is situated.”

The Income Tax Act sets out the source principle for non-resident persons as follows:

35.(1) A person shall, upon payment of an amount to a non-resident person not having a permanent establishment in Kenya in respect of –

(a) a management or professional fee;

(b) a royalty; (…)

(e) interest, including interest arising from a discount upon final redemption of a bond, loan, claim, obligation or other evidence of indebtedness measured as the original issue discount; (…)

(i) consultancy, agency or contractual fee,

which is chargeable to tax, deduct therefrom tax at the appropriate non-resident rate.

Source rules, both nationally and internationally, often rely on a distinction between different types of income or the ability to characterise a specific type of income. However in the context of E-commerce, income characterisation problems often occur. Digital and online commercial activities bring new challenges in a variety of areas including taxation. In Republic v Commissioner of Domestic Taxes (Large Taxpayers Office) Ex parte Barclays Bank of Kenya Limited, the dispute concerned whether the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) was entitled to demand withholding tax from Barclays Bank on payments made: (1) to Card Companies such as VISA International Services Association, MasterCard Inc., and American Express Ltd.; and (2) as an Interchange Fee to other Banks referred to as the Issuers. The court held that KRA ought to have clearly identified the category in which the tax was sought, and that their decision to broadly state that the payments amounted to professional or management fees did not meet the level of clarity required in taxation.

Similarly in the case of Kenya Commercial Bank Limited v Kenya Revenue Authority [2016] eKLR, KCB entered into a Software Licence and Service Agreement with Infosys Technologies Limited (Infosys), a company incorporated in India. By the agreement, Infosys agreed to provide banking software packages and allied services including professional services. KRA notified KCB that it was liable to pay withholding tax on Infosys payments, interest and incidental expenses. The tax collector advised KCB to pay tax which stood at Kshs. 57,150,556/-. The court held that the issue was that there was no clear categorization of the payments. There is no ambiguity. The issues framed before the local committee shows that “royalties” referred to licence fees for use of the software.” Another case to consider is Stanbic Bank of Kenya v Kenya Revenue Authority [2009] eKLR where the court held that the services rendered online by Reuters International, by providing data to the bank, fell under the ambit of professional fees and were therefore taxable.

With regard to tax deductions at source, section 35 of the Act reads as follows:

35.(3) A person shall, upon payment of an amount to a person resident or having a permanent establishment in Kenya in respect of –

(a) a dividend; or

(b) interest (…)

(g) a royalty;

which is chargeable to tax, deduct therefrom tax at the appropriate resident withholding tax.

Section 2 of the Act states that “permanent establishment” in relation to a person means a fixed place of business in which that person carries on business and for the purposes of this definition, a building site, or a construction or assembly project, which has existed for six months or more shall be deemed to be a fixed place of business” This raises the question: If business is conducted through a website or a server, can these be considered to be a ‘fixed place of business’ or ‘permanent establishment’?

An Internet website is what appears on the computer screens when a web address is accessed. It consists of the software and electronic data stored on the server and allows an enterprise to interact directly with its customers. A website is a virtual office. It is intangible property and does not provide a regular link between the place of business and a specific physical geographical point. It cannot be deemed to be a fixed place of business for purposes of the meaning of the term: permanent establishment.

A server, on the other hand, is automated equipment on which an Internet website is stored and through which the website is accessible. It has a physical location, and if it is used regularly for enterprise business it might constitute a permanent establishment if it is at the disposal of the enterprise for that purpose. When an enterprise conducts its business through a website that is hosted on the server of an Internet Service Provider (ISP), such hosting arrangements do not result in the server and its location being at the disposal of the enterprise even though the website of the enterprise is hosted on a specific server at a specific location. This is because the enterprise does not have a physical presence at the location of the server, since the website through which it operates is not tangible. However, if the enterprise owns (or leases) and operates the server on which the website is stored and used, then the place where that server is located could constitute a permanent establishment, as the server and its location is at the enterprise’s disposal. Even if the enterprise has a server at its disposal, the server must be fixed at some location to constitute a permanent establishment.

In other words, the server needs to be located at a certain place for a sufficient period. Even if the enterprise has control over the server that is located at a fixed place of business in another country, the meaning of the term: permanent establishment still requires that the business of the enterprise should be wholly or partly carried on through the place where the server is located. Further still, a server will not be considered a permanent establishment of the enterprise if the activities carried on through a server in a given location are restricted to preparatory or auxiliary activities. Such activities would include the provision of a communication link between supplier and customer, advertising of goods or services (eg a display of a catalogue of certain products), relaying of information through a mirror server for security and efficiency purposes, gathering market data for the enterprise and supplying such information. However if such functions go beyond preparatory or auxiliary activities in that they form the main function of the enterprise and they are an important and significant part of its business activities, then a permanent establishment will be deemed to exit.

From the above, it can be concluded that a permanent establishment based on a fixed place of business will only be deemed to be present when the enterprise is carrying on business through a website that has a server at its own disposal and in a fixed location, and the business of the enterprise is not of a preparatory or auxiliary nature. However, very few enterprises carry on business through their own servers and consequently they would not be liable to tax as they will be considered not to have permanent establishment in that country. In this regard e-commerce poses challenges that can provide opportunities for the avoidance of taxes.

The Value Added Tax Act has specific sections that may be applicable to e-commerce transactions. For instance section 8 of the Act reads as follows:

8.(3) In this section—

“electronic services” means any of the following services, when provided or delivered on or through a telecommunications network—

(a) websites, web-hosting, or remote maintenance of programs and equipment;

(b) software and the updating of software;

(c) images, text, and information;

(d) access to databases;

(e) self-education packages;

(f) music, films, and games, including games of chance; or

(g) political, cultural, artistic, sporting, scientific and other broadcasts and events including broadcast television.

With regard to the place of supply of services, the VAT Act states as follows

8.(1) A supply of services is made in Kenya if the place of business of the supplier from which the services are supplied is in Kenya.

(2) If the place of business of the supplier is not in Kenya, the supply of services shall be deemed to be made in Kenya if the recipient of the supply is not a registered person and—

(a) (…)

(d) the services are electronic services delivered to a person in Kenya at the time of supply; or (…)

Apart from the fact that e-commerce challenges a country’s jurisdiction to tax income in certain instances, it also encumbers the enforcement of tax laws. The ability to collect taxes is based on the ability to: identify and locate taxpayers (the tax system must have access to the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s assets to ensure the collection of taxes payable); identify and verify taxable transactions; establish a link between taxpayers and their taxable transactions. E-commerce transactions not only obscure the identity and location of the buyers and sellers who participate in Internet- based transactions, but often make them irrelevant. Anonymity is a unique feature central to e-commerce transactions. The use of electronic money or digital cash enhances this feature and leads to increased enforcement problems as there is usually no trace of the identity of the person spending the electronic money.

There is no international organization with a specific role of supervising the operation of tax among nation states. However the OECD has played a leading role in promoting reform efforts in the international income arena via its model tax treaties and commentaries to treaties. The EU adopted directive 2002/38/EC which is lauded as a great step in modifying rules germane to VAT and especially addressing the non-neutrality between an online trader and offline trader and an EU and a non-EU supplier of electronic services. The directive sufficiently addresses for instance, internet challenges associated with internet such as identifying the location or residence of a consumer supplier. Unlike the US, the EU found itself in the position of being a net importer of digital goods and services. The EU quickly realized that, foreign taxpayers no longer had to maintain a physical presence in the EU in order to do business on European markets. Kenya like the EU is a net importer of digital goods and services.

In conclusion, countries are caught up in the dilemma of either not taxing e-commerce and risk the depletion of their tax bases or taxing e-commerce and risk the stifling of its development. There is need to come up with a feasible way of taxing e-commerce transactions so that the tax avoidance opportunities that e-commerce has created can be curbed.