“anything under the sun that is made by man [is patentable]”

– US Supreme Court in the case of Diamond v. Chakrabarty 447 US 303 (1980)

“From where does a man derive his right to possess something, and to refuse the whole world his right of ownership? This right originates from only one factor; the fact that man is nobody’s property. He owns himself and cannot be someone else’s possession. If, therefore, man possesses himself, it is clear that his wealth, his intellect, and his ability cannot be someone else’s property. So, whenever he uses his intellect, his health and his ability to make anything, that thing becomes his property”

– Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, “Freedom and Unity/Uhuru na Umoja” (1966) (cited at #CIPITConf by @IPKenya)

“Anything that won’t sell, I don’t want to invent. Its sale is proof of utility, and utility is success.” – Thomas A. Edison. (cited at #CIPITConf by @HKMLegal)

“When we work, natural law says we have the right to own our work. To let others steal this is to destroy the basis of civilization, to cast us into slavery. If I cut a tree and make a table, it is mine. If I write a story, it is mine. If I invent a new compression algorithm, it is mine. When someone takes my ideas, it is theft, and a just society must punish theft, or it falls apart. Software patents are thus a natural and necessary protection for original ideas.”

– Peter Hintjens. (cited at #CIPITConf by S. Kiptinness)

During CIPIT’s 2-day conference (#CIPITConf) on the patentability of software in Kenya, none of the speakers appeared to advocate for an outright position for or against software patents. Instead, all the presenters at #CIPITConf did their best to elaborate on the pros and cons of patents generally and software patents in particular.

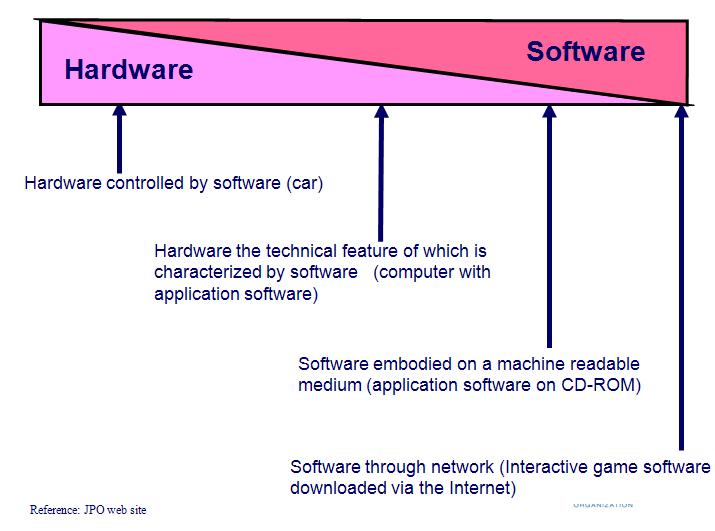

With regards to the patentability of ICT inventions, the patent experts at #CIPITConf from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the Kenya Industrial Property Institute (KIPI) both seem to agree that one is most likely to be granted a patent for a hardware controlled by software and least likely to be granted a patent for a software embodied on a machine readable medium or through a network.

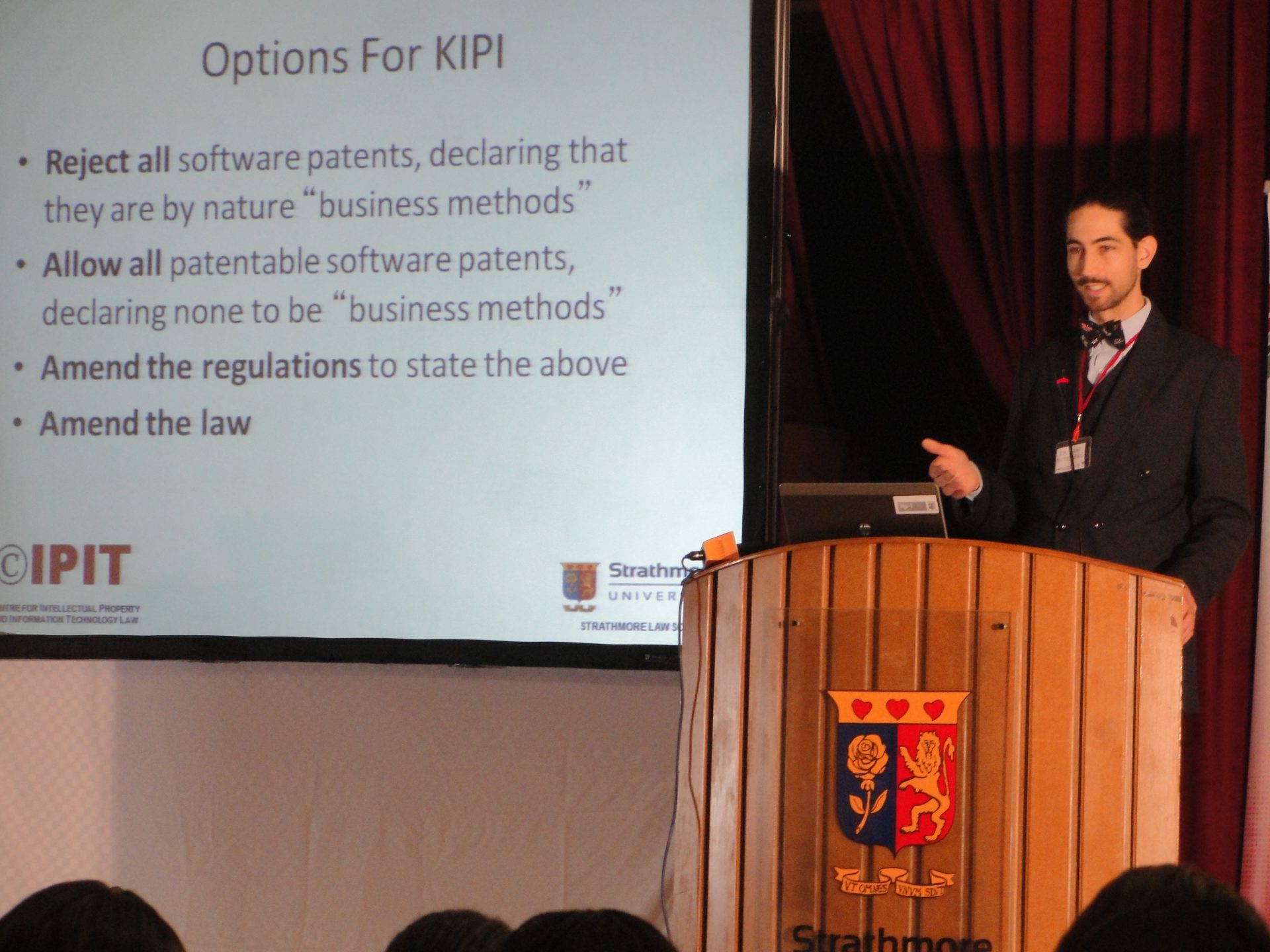

Therefore the decision Kenya needs to make is where to draw a line between unpatentable computer programs and patentable inventions that embody, apply or use the unpatentable computer program. In this regard it was noted by participants at #CIPITConf that there’s a lack of administrative and judicial interpretations on the exclusions from patentable subject matter provided for under section 21 of the Kenya Industrial Property Act. Thus, Kenya needs to develop it’s own clear tests for distinguishing non-patentable software and patentable software-implemented inventions. These tests will only develop from a large and consistent volume of software patent applications being filed at KIPI coupled with fervent litigiousness on the part of unsuccessful software patent applicants.

In this regard, CIPIT may decide to play an active role in assisting software developers in preparing their patent applications especially in the area of drafting claims. CIPIT may also be willing to provide an important forum for developers to interact with potential users and buyers of their products and get ideas on what kind of solutions are in demand.

Would Software Patents Be Harmful or Helpful to Kenya?

It was agreed at #CIPITConf that the best way to encourage innovation is to protect the expression of the ideas of the innovators which in turn leads to addition in the public domain of information which can prove helpful and sometimes completely transformational to society at large. Without the promise of the protection innovators will never disclose their secrets to the society’s detriment. Innovators who put in hard work require a just and fair compensation for their hard work, one way of doing this is by giving them exclusive rights to exploit their IP for a certain period.

Start-ups are the predominant vehicle for software developers entering the ICT industry. The interaction between start-ups and IP rights exists at all stages of start up’s life-cycle: establishment, growth and/or exit from the business. Although applying for software patents may seem like a good idea for start-ups, there are important factors to be considered, namely, the cost of filing, duration of application process and possible litigation in the event of infringement. Whether or not Kenya decides to allow software patents, it was been argued that Kenyan inventors should seek to file for patents internationally at PCT, USPTO and EPO, where lots of people will notice them and in turn this could attract investment to Kenya.

However, some of the reasons put forward at #CIPITConf why software patents may be harmful are the following:

1. Software patents are often pursued by large and wealthy corporations who splurge their cash on prosecuting and defending their patents/increased litigation;

2. The large percentage of ownership of software patents by large firms disadvantage smaller firms and labs thus stifling innovation for fear infringement, proprietary software militates against open source;

3. Cost of filing a patent is prohibitive; the patent application process and eventual grant is interminable;

4. Sometimes patents are objected to by some in the tech community on grounds that some of the innovations can be easily developed by anyone in the tech community and independently of each other as such they are trivialities and therefore patenting would lead stifling innovation

5. Duration of patent is too long, therefore reduces competitiveness in society; impacts negatively on competition by exclusive agreements to restrict usage, control price and even worse to stop others from innovating on top of existing products even though the patent owner has never brought it into production, until the patent has expired. Thus prices can never be competitive.

However, #CIPITConf participants acknowledged that software patents may have important advantages, especially for a developing economy such as Kenya. The most compelling argument advanced for software patents in Kenya is the solo inventor scenario. This particular scenario is best exemplified by the on-going MPesa debate. Who owns it? Who “originally” developed it before it got into Safaricom’s hands? And most importantly, which IP regime will provide adequate protection for ICT inventions?

While many have argued that software generally (drawing from the MPesa experience) would be best protected under patents, Dr. Rutenberg has argued differently. In an article he wrote earlier this year titled: “Safaricom, mPesa and business method patents: another view”, Rutenberg says:

“Having been involved in drafting business method patents, I can report that they are a tragic misuse of the patent system. I can make a very strong case for allowing patent protection of, say, pharmaceuticals or medical devices. I cannot think of any good arguments for allowing software or business method patents. They stifle innovation but, in the end, actually provide little protection for the patentee. They cause entrepreneurs to spend money and time on something relatively unimportant (getting patent protection) at the expense of what is truly important (building a brand name and a customer base).

I have never met a software designer or web developer in the US in favour of such patents, and most say that they hate them. The only people I know who like these patents are the lawyers who write them. I wish that the US would follow the Kenyan system, and not allow software and business method patents. I sincerely hope that they do not change the Kenyan patent law to allow them!”

However several arguments have been advanced in favour of software patents generally. South African IP practitioner Darren Olivier argues thus:

“On the question of software and business method patents – there is so much innovation in the tech space and since copyright seems to offer little real protection I wonder whether we undermine the importance of patents by excluding them on software as a principle. Using the USA as an analogy is useful but one has to bear in mind that we are talking of a developed country where litigating patents has developed to a business in its own right. In Kenya (and Africa) I see a case for affordable patent protection for software patents to support our tech entrepreneurs yet I do not deny that it woud need careful implementation because it could so easily do the opposite.”

An important observation made by Mr. Douglas Gichuki, Research Fellow and Assistant Lecturer at Strathmore Law School was on the importance of branding over patenting in respect to protection and promotion of expressed ideas in ICT inventions. He argues that software developers may feel that patenting is the only way to protect such ideas without realising that patenting does not grant monopolies over the ideas, thereby excluding anyone else from using the same ideas in different ways. To illustrate this, Gichuki gave the example of CIPIT, the first IP institution of its kind in the entire region. He reckons that it wont be long before other Law Schools “copy” CIPIT, therefore branding CIPIT as the first and the best IP Centre would be far more beneficial than preventing others from using the CIPIT concept.

Other than trademarks, the participants at #CIPITConf were also quick to point out that copyright protection is also available and equally useful for protection of ICT products. Copyright law in Kenya provides protection for software as original works of authorship manifested in a tangible medium of expression. Protection, however, does not extend to the underlying idea embodied in the copyrighted software, or to the medium or device used to express the software.

It was argued at #CIPITConf that copyright law currently provides the most convenient available means of encouraging software development because protection is easily obtained and at a minimal cost. Once software, which is an original work of authorship, is fixed in a tangible medium, copyright protection exists automatically. Although the law requires payment of a fee and the deposit of the work to be copyrighted, failure to perfect registration will not affect rights in the copyrighted material.

The minimal expense and speed with which copyright protection of software is attained is very advantageous. First, the avoidance of long administrative procedures to obtain rights in software prevents the wastage of a significant portion of the commercial life of software. Secondly, Copyright law allows numerous independent programmers, who are unable to afford costly forms of protection, such as provided by the patent law, to obtain protection.

In the final analysis, the decision by Kenya whether to patent software or not will be made once there’s a critical mass of software patent applications pending before the patent examiners at KIPI or under review before the Industrial Property Tribunal or on appeal before the High Court.

In the meantime, CIPIT’s goal is to help Kenya effectively use domestic and international intellectual property rights by building brands, competing in the market, and attracting investors on an international scale. As the CIPIT Director puts it: “We are not pro-IP, we are pro-Kenya!”