A Review of the Communications Authority Guidelines for Dissemination of Political SMS Text Messages and Social Media Content

- Victor Nzomo |

- July 18, 2017 |

- CIPIT Insights,

- Information Technology,

- Social Media and the Law

By Francis Monyango**

In the run-up to the 2013 elections, Safaricom announced that it would control political messaging distributed via its network. This measure was put in place to avoid unnecessary attacks on individuals, their families and ethnic communities. The giant mobile network operator wanted to ensure that the bulk political SMS sent through its platform would not fall foul of the laws of Kenya. By publishing its own guidelines on bulk SMS of a political nature, Safaricom was working within its legal boundaries of leverage. This move was inspired by the Electoral Code of Conduct, which was part of the 2011 Elections Act that specifically prohibited hate speech in political campaigns. These guidelines were met by furor from the political class but the media peace campaigns drowned their voices.

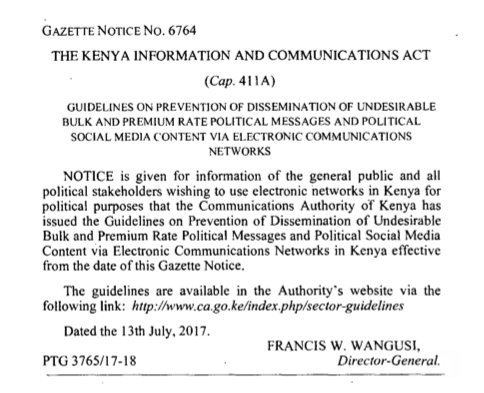

In June 2017, Communication Authority of Kenya (CA) has picked the cue from Safaricom and collaborated with the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) to prepare guidelines on the dissemination of political messages via electronic networks. Being an election year, there have been widespread fears that inciting ethnic hate may be spewed through text messages and online by social media users. Therefore these guidelines have been received by mixed reactions. Many are glad that there will be some sanity in political messaging while some stakeholders such as Bloggers Association of Kenya (BAKE) have expressed their dissatisfaction with the amount of time that was allocated for public participation.

While the guidelines may have been issued in good faith, a perusal of the guidelines shows that there are sections which may be challenged as unconstitutional. The Constitution of Kenya 2010 acknowledges the right to freedom of expression. This right is not absolute as it contains limitations listed in Article 33 (2) as follows:

33 (2) The right to freedom of expression does not extend to—

(a) propaganda for war;

(b) incitement to violence;

(c) hate speech; or

(d) advocacy of hatred that (i) constitutes ethnic incitement, vilification of others or incitement to cause harm; or (ii) is based on any ground of discrimination specified or contemplated in Article 27 (4).

(3) In the exercise of the right to freedom of expression, every person shall respect the rights and reputation of others.

Based on these limitations, the High Court of Kenya has on numerous occasions declared several statutory provisions unconstitutional for the mere reason that they are beyond the scope of Article 33(2). Most notably, the court has struck down statutory provisions that were in the past used to persecute bloggers and silence political dissents. In the following paragraphs, the clauses of the Guidelines will be analysed, starting with the clauses that are wins for the human rights cause then finish off with some of the controversial clauses that threaten the enjoyment of fundamental rights.

Jurisdiction

While explaining the background of the Guidelines and authority to impose the guidelines, the Communications Authority of Kenya relied on sections 23 and 25 of the Kenya Information Communications Act (KICA) to show that it is mandated to protect the interest of all users of telecommunications services in Kenya. This is in respect to pricing, quality and the granting of licenses with conditions including specification of services.

These sections of the law read as follows-

23 (2) Without prejudice to the generality of subsection (1), the Commission shall

(a) Protect the interests of all users of telecommunication services in Kenya with respect to the prices charged for and the quality and variety of such services…

25 (3) A licence granted under this section may include conditions requiring the licensee

(a) To provide the telecommunication services specified in the licence or of a description so specified…

It is important to note that while Communications Authority has mandate over telecommunication services in the country, the law is clear that this mandate extends to all entities that it licences as the regulator. This was clarified in the landmark case of Geoffrey Andare v Attorney General & Director of Public Prosecutions (2016). In this case, the learned Mumbi J stated that the Act may not have been intended to apply to individual users of social media or mobile telephony. This is because section 24 of KICA deals with the issuance of telecommunication licenses and individuals who post messages on Facebook and other social media do not have licenses to “operate telecommunication systems” or to provide telecommunication.

Clause 1.2 of the Guidelines states that they are applicable to licensees, broadcasters, Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNOs), Content Service Providers (CSPs) and Mobile Network Operators (MNOs). Because these licensees tend to have collaborative arrangements with other stakeholders such as bloggers, Social Media Services Providers, the guidelines may apply to them among others.

The good

Clause 7 of the Guidelines prohibits CSPs from sending unsolicited bulk messages to people who have not subscribed for the service. This is good because there have been complaints by people who have received unsolicited text messages from political candidates. Questions on customer privacy rights and whether telecommunication companies or content service providers were selling their customers contact details have been raised. The Guidelines prohibit the sale of that data and they require service providers to have consent or subscription from the customer allowing them to send political messages.

Part II of the Guidelines states how political messages posted on social media should be. The clauses in this part call for honesty in content publishing as the content authors will be held responsible for their content. This part also prohibits hate speech according to the Constitution and the National Cohesion and Integration Act. All political advertisements on social media platforms are expected to adhere to Kenya’s electoral laws.

The social media guidelines prohibit publishing of a person’s private information without their consent. This is a good guideline as it is in adherence to Article 31 of the constitution which provides for the right to privacy. This may also be used to rein in social media users who use personal information to bully individuals online like Rwanda’s presidential candidate Diane Shima whose nude photos were leaked online.

The guidelines offer a safe habour for publishers of political content on social media platforms. It allows them to liaise with NCIC when unsure whether the content they want to publish is inflammatory. NCIC is required to reply to these queries within 24 hours which is a good thing.

The Questionable

On social media content, the guidelines on language and tone require all content to be written using a civilized language that avoids a tone and words that are defamatory. In light of the judgment of the Andare case, this provision appears to be vague as far as the criteria as to what constitutes ‘civilized language’ is concerned. This guideline seems to re-introduce criminal defamation that was declared by the unconstitutional in the case of Jacqueline Okuta & another v Attorney General & 2 others (2017). For defamation, the individual who suffered damage is the one with locus to raise a complaint. Political messages which are usually very charged and muddy. Propaganda is countered using propaganda. No one has clean hands in this arena, hence the aggrieved never go for equity.

The guidelines also requires political content authors on social media to authenticate and validate the source of their information. This may as well be the Authority’s move to rein in fake news and speculation posted on social media platforms. Care should be taken as, it borders on unconstitutionality since it is not within the limitations stipulated in Article 33 (2).

The guidelines also require all political content on social media be polite, truthful and respectful which is not only hard to police but is also too controlling. Social media sites have community standards where users who go overboard are reported and their accounts subsequently suspended. According to Facebook’s Head of Public Policy for Africa, Ms. Ebele Okobi, there is under-reporting in Sub-Saharan Africa. She blames this on lack of awareness among users in this region on how to report content that breaches their community standards.

Legally, section 132 of the Penal Code law that was used to charge many bloggers for disrespect or undermining the authority of a state officer was declared unconstitutional by the High Court in the case of Robert Alai v The Hon Attorney General & another (2017). This makes it hard for the regulator and NCIC to legally decide what should be rendered respectful.

While these guidelines may have been promulgated in good faith, the general feeling is that there are enough laws to rein in hate speech. From the Constitution to the National Cohesion and Integration Act, laws are there but the will to implement them is lacking. The balance between free speech and hate speech is really thin. Not all uncomfortable statements are hate speech according to the law.

**Francis Monyango is online at: www.monyango.com and on twitter: @franc_monyango