Intellectual Property and Employment: Did Vodacom South Africa "Steal" Please Call Me From Ex-Employee?

- Victor Nzomo |

- August 8, 2013 |

- CIPIT Insights

Many years ago, this blogger landed in South Africa as a wide-eyed 20-something law student. With a meager budget to survive on, many of my classmates and South African friends may have forgiven me for making abundant use of PCM. PCM is short for “Please Call Me”, a revolutionary service whereby Vodacom allowed its subscribers to send FREE messages to anyone on all South African networks, asking them to call you. PCM was a great way of getting in touch when you didn’t have any airtime to make calls or send SMSs. It suffices to say that this nifty PCM function really came in handy in cases of emergencies.

Presently, media reports indicate that Vodacom is embroiled in a David-vs-Goliath law suit with a former employee who claims that he came up with the idea of PCM and is now seeking compensation from the telecommunications giant. The ex-employee’s name is Nkosana Makate and from various media reports, this is what we know so far.

Makate’s case against Vodacom

In November 2000, Makate, then an accountant at Vodacom, presented the idea of PCM to his immediate superior, Lazarus Muchenje. Makate says the idea came to him because of difficulties in communication between him and his girlfriend at the time who was a student and often could not afford to contact Makate. At the time he thought his idea would have have immediate tangible benefit for Vodacom subscribers but it would also have a massive benefit for Vodacom.

Makate claims his idea caught the attention of the then head of product development at Vodacom, Philip Geissler promised to facilitate remuneration negotiations between Makate and the company once he submitted the idea and once it was developed and its technical and commercial feasibility were ascertained.

Media reports also indicate that an e-mail sent to Makete from Geissler in which the latter allegedly said: “As for rewards, all staff are expected to assist the company. As for you. I will speak to Alan [Knott-Craig, then CEO of Vodacom]. You have my word.”

Makate is now in court seeking to compel Vodacom to discuss reasonable compensation

Vodacom’s defense

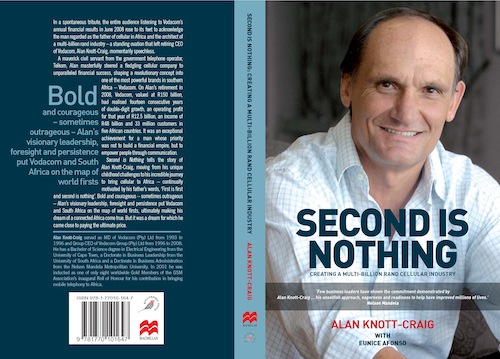

In his biography “Second is Nothing”, former Vodacom CEO Knott-Craig writes that the PCM idea came to him while standing on his balcony and witnessing two security guards trying to communicate with each other by calling each other then quickly hanging up.

Both Vodacom and Knott-Craig are adamant that Makate is not entitled to any compensation, and the individuals who entered into any agreements with him (namely Geissler) were not authorised to do so. During cross examination, Knott-Craig testified that Geissler’s alleged agreement with Makate was made despite the fact that Vodacom did not compensate employees for their ideas above normal remuneration.

It is reported that Knott-Craig testified that Vodacom never had a profit-share or revenue-share agreement with employees who introduced new ideas:

“This particular promise of sharing revenue within a company is not normal. I would’ve been surprised that he [Makate] believed that a company would share its revenue on an untested product…To lead Makate to believe that [the reward he wanted] is beyond what the company could ever give.”

Knott-Craig is currently CEO of Vodacom’s smaller competitor, Cell C.

Comments:

From an IP perspective, this case illustrates some of the issues in protecting intellectual property in the employment context. Ideas are not protected under IP law. Makate claims he was the first person to come up with the idea of the PCM function which he later presented to his superiors and was promised compensation as a reward. The question begs, in what format was the PCM idea presented?

If Makate had taken his idea on the PCM service and expressed it in a written report or concept paper or presentation in 2000, that written work would be the subject of copyright law. Generally, copyright law confers ownership on the author however in the employment context, copyright law makes an exception. The so-called “work made for hire” doctrine provides that the employer automatically owns the copyright in an employee’s work, IF the employee creates that work within the course and scope of his employment.

It is important to note that in the present case, Makate was a junior accountant at Vodacom when he claims to have come up with the idea of the PCM service. The question then begs, was it within an Vodacom accountant’s scope of employment to develop a product/service like PCM?

In this context, the prudent employer (XYZ Ltd) will have crystal clear clauses in its employment agreements detailing the meaning of intellectual property subject matter created outside the scope of employment.

Consider the provision below:

XYZ Ltd acknowledges and agrees, in accordance with applicable laws, that any creations or inventions:

(a) that you develop entirely on your own time; and

(b) that you develop without using XYZ Ltd’s or its subsidiaries’ equipment, supplies, facilities, or trade secret information; and

(c) that do not result from any work performed by you for XYZ Ltd or its subsidiaries; and

(d) that do not relate, at the time of conception or reduction to practice, to XYZ Ltd’s or its subsidiaries’ business or products, or to XYZ Ltd’s or its subsidiaries’ actual or demonstrably anticipated research or development,

will be owned entirely by you, even if developed by you during the time period in which you are employed by XYZ Ltd.

The prudent employer will also be keen to clearly set out in its employment agreements, the conditions upon which it will own IP subject matter developed by its employees by setting out its definition of “within the scope of employment”.

Consider the provision below:

You agree that all Inventions/Creations that:

(a) are developed using the equipment, supplies, facilities, or Proprietary Information of XYZ Ltd or its subsidiaries; or

(b) result from or are suggested by work performed by you for XYZ Ltd or its subsidiaries; or

(c) are conceived or reduced to practice during your employment by XYZ Ltd and relate to the business and products, or to the actual or demonstrably anticipated research or development of XYZ Ltd or its subsidiaries (“XYZ Ltd Inventions/Creations”),

will be the sole and exclusive property of XYZ Ltd, and you will and hereby do assign all your right, title and interest in such XYZ Ltd Inventions/Creations to XYZ Ltd. You agree to perform any and all acts requested by XYZ Ltd, if any, to perfect this assignment. (…)

In the Kenyan context, this blogger highlighted a similar case pitting the national tax collector, Kenya Revenue Service (KRA) against one of its employees, Samson Ngengi. While employed at KRA, Ngengi claimed that he developed the Geo-spatial Revenue Collection Information System (GEOCRIS), a software that maps property location, ownership and building details, as well as the tax status of a taxpayer, providing an effective tool for collecting rental income levies.

In 2012, Ngengi successfully moved to court for interim orders barring KRA from dealing in GEOCRIS or developing any similar system until full hearing and determination of Ngengi’s case for compensation for KRA’s use of GEOCRIS and whether KRA should issue a technovation certificate to Ngengi in respect of GEOCRIS. This case is still on-going. However Ngengi’s case differs from Makate’s case because in the former case, the employee took his idea and developed it into a product that was later claimed by his employer.