Kenya's Patent Wars: Sanitam Services vs Everyone

- Victor Nzomo |

- January 27, 2014 |

- CIPIT Insights,

- Patent

“The [matter] before us focuses on a branch of law which has scanty litigation and therefore minimal jurisprudential corpus in this country, but which has exploded on the world stage since the end of the 19th Century when the international community formed two international unions to promote it – Intellectual Property” – Court of Appeal in Sanitam Services East Africa Limited v Rentokil Limited 2006

IPKenya’s friend and the Chief Patent Examiner at KIPI informs us that the Industrial Property Tribunal has recently made a ruling revoking patent no AP 773 granted to Sanitam Services with respect to is sanitary bin. This brings to conclusion a long and arduous battle fought by Sanitam against several manufacturers since the late 90s to protect its sanitary bin invention.

This blogpost chronicles the various court cases brought by Sanitam both nationally and regionally to assert its patent rights. It is argued that Sanitam has made an enormous contribution to advancing intellectual property law jurisprudence and raising pertinent issues in the area of patent prosecution and litigation.

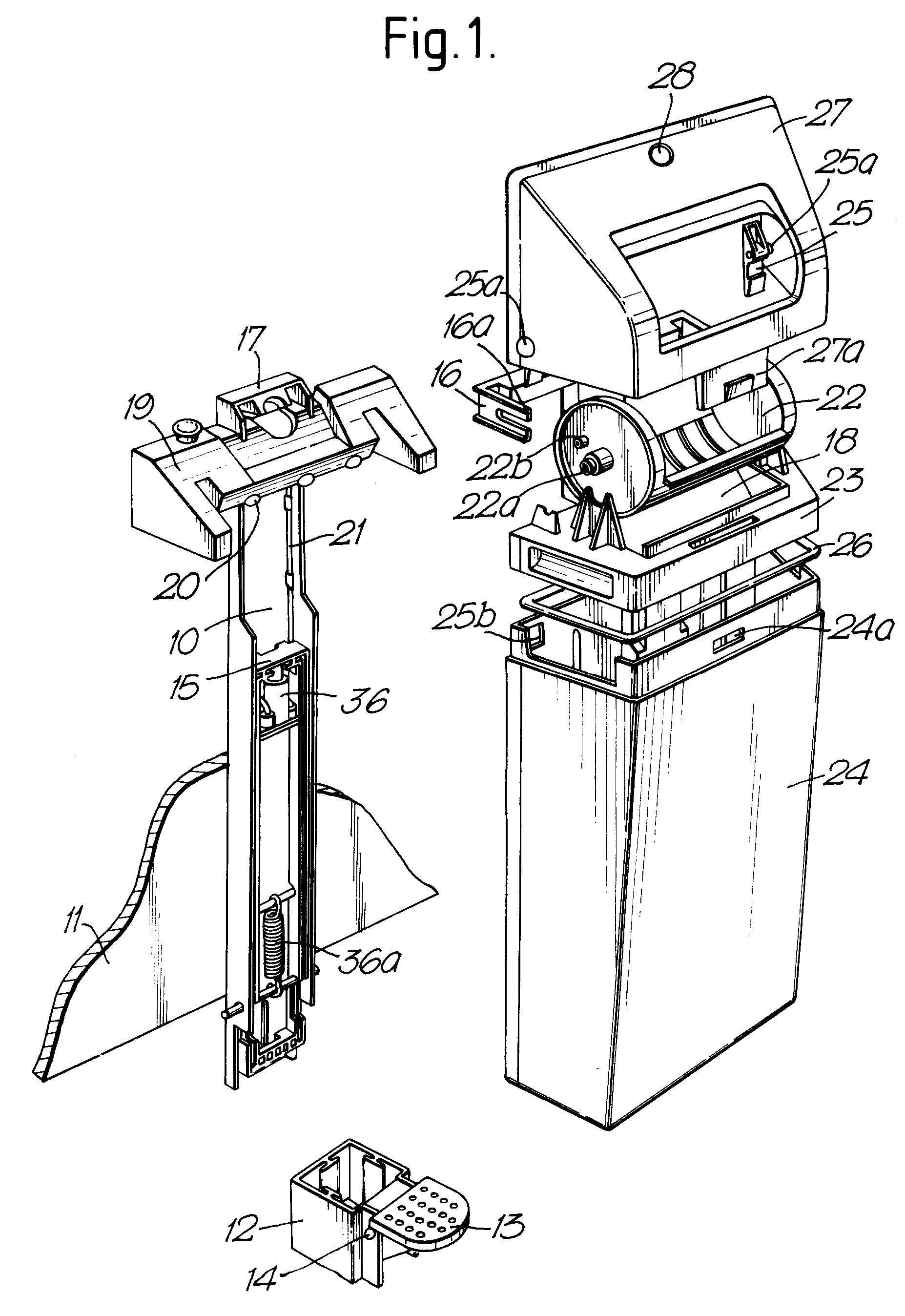

In 1997, Sanitam alleges that it designed and invented a foot-operated litter/sanitary disposal bin for use in the hygienic storage and disposal of sanitary towels, tampons, surgical dressings, serviettes and other waste material. One of the novel features of the sanitary bin invention claimed by Sanitam is that it has a flap opening to receive the waste and covering the contents inside so that whoever is operating it cannot see the contents inside even when using it and also the odour is minimized by the invention. This invention titled “Foot Operated Sanitary/Litter Bin” (ARIPO patent No AP 773) was granted and issued in October 1999 by the African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation (ARIPO).

In Sanitam Services (EA) Ltd v. Anipest Kenya Ltd & Anor Civil Case No. 1898 of 2000, the late Justice Peter John Smithson Hewett sitting in the High Court dismissed a suit filed by Sanitam seeking an injunction to prevent Anipest from carrying out any acts exclusively granted to an owner of a patent under section 36 of the Industrial Property Act of 1989 (now repealed). PJS Hewett’s ruling dated March 2001 is significant as it addresses a major shortcoming in the operationalisation of the repealed Industrial Property Act, namely the absence of the Industrial Property Tribunal over 10 years after the Act came into effect. More significantly, this ruling offers the first critical analysis of Sanitam’s novelty claims in the sanitary bin invention.

The learned judge, reviews the abstract of Sanitam’s abstract and states:

“Assuming as I do, that the ARIPO rules of patentability are the same as or very similar to those of Kenya, I return to the abstract to see what it tells me particularly about novelty.

“A foot operated litter/sanitary disposal bin comprising a container (1)[”:] nothing novel there;

“closeable by a cover (2)”: nothing novel there either:

a disposal lid(3)”-still nothing novel:

“at the top, with the disposal lid being displaceable by a foot operated pedal (4)”: still nothing novel:

“and a lift lever (5)…” nothing novel,

“to move between open and closed positions. The bin is defined such that the user cannot see the contents of the container, waste scavengers cannot have access to the contents, emission of unpleasant odour is reduced and the contents cannot spill out if the bin is overturned.”

I only have to look at this matter prima facie. Are all these attributes prima facie novel. Prima facie they seem to be to me on evidence many many years old: certainly they do not seem to me to be prima facie novel-which is all I have to consider.”

This blogger submits that this finding by the learned judge paved the way for other litigants and manufacturers to question the validity of AP 773 which has now finally culminated in the revocation of the patent by the Industrial Property Tribunal.

In Sanitam Services (EA) Ltd v Rentokil (K) Ltd & Anor Civil Suit No. 58 of 1999, Sanitam moved to the High Court orders of permanent injunction to restrain Rentokil Ltd and Kentainers Ltd from manufacturing, selling and distributing the sanitary bins which infringed on its patent. Rentokil and Kentainers contended that they were already manufacturing the product before the plaintiff had obtained a patent over the invention. Therefore they argued that Sanitam could not claim exclusive rights over the product.

In Justice Onyango Otieno’s ruling delivered in May 2002, the court dismissed the Sanitam’s suit holding that it failed to prove that it had obtained a patent over its foot operated sanitary bin. In addition, Sanitam was already distributing its product 2 years prior to the registration of the patent. Therefore Rentokil and Kentainers had not infringed Sanitam’s rights by creating a similar product and obtain a market for it.

This case is significant for at least three main reasons. First and foremost, the court upheld patents granted by ARIPO as valid and enforceable within Kenya pursuant to the latter’s obligations under the ARIPO Protocol.

Secondly, although the court made several obiter dicta remarks regarding the novelty of Sanitam’s bin invention, the court ultimately held that Courts of law must defer to the National Patent Office KIPI and the Regional Patent Office ARIPO on questions pertaining to the patentability of any invention in dispute. According to the court, KIPI and ARIPO are the bodies with the technical know-how to investigate the patentability or otherwise of inventions and that in the present case, one of the two had presumably investigated the invention and found it fit to grant a patent for it. Therefore whoever challenges the grant of any patent must do so before these institutions and not in court.

Finally, the court made an important finding on the burden of proof in matters relating to infringement of industrial property, particularly where the industrial property in question is unregistered. In the case of Sanitam, the court found that since there was no patent in existence at the time a similar bin to Sanitam’s was produced, Sanitam could not claim patent infringement.

In Sanitam Services (EA) Ltd v Rentokil (K) Ltd Civil Appeal No. 228 of 2004, Sanitam moved to the highest court in the land (at the time), the Court of Appeal, seeking for the Court to reverse the above decision of the lower court (High Court) in favour of Rentokil. Sanitam’s appeal against the High Court Decision was partially successful as the Court of Appeal granted Sanitam an injunction for the lifetime of the disputed patent AP 773 with effect from 16th December 1999. However the Court of Appeal did not award Sanitam any damages thereby concurring with the High Court’s determination that Sanitam had not discharged the onus of proof.

In 2008, ARIPO published an entry in its Journal to the effect that Sanitam’s patent AP 773 had lapsed for failure to pay annual fees. Soon thereafter, Sanitam brought an appeal against the decision of the ARIPO Patent Office removing its patent from the Register due to non-payment of annual maintenance fees. It was argued that maintenance fees were consistently late since the patent was granted in 1999. The ARIPO Appeal Board concluded that both parties were to blame for the delays in the payments; the Office had failed to send reminders, which it is required to do under the Harare Protocol. Therefore the Office was urged to strictly observe the provisions of the Protocol particularly those pertaining to time limits, information delivery and processing procedures.

Consequently, the Appeal Board ordered the patent be reinstated in respect of the designated states, including Kenya and Uganda.

In Sanitam Services (EA) Ltd v Bins Nairobi Services Ltd Civil Suit No. 597 of 2007, Sanitam successfully moved the High Court for orders of injunction against Bins restraining the latter from a host of acts alleged to be infringing on Sanitam’s patent AP 773.

The issue for determination by the court was found to be whether Sanitam had established a case to entitle the court to grant the orders of injunction sought. In making this finding, the court reaffirms the earlier position of the High Court in the Rentokil case that the court is not the right institution to question the patentability of any invention in dispute and is bound to respect a patent duly issued by KIPI and/or ARIPO.

Therefore with respect to Sanitam’s onus of proof, the court found that the latter had proved that it had a valid patent ARIPO Patent no. AP 773, which was infringed by Bins through the acts of offering for sale or hire of foot-operated sanitary bins without Sanitam’s authorisation.

In Rentokil Initial Kenya Ltd v Sanitam Services (EA) Ltd Civil Suit No. 702 of 2008, Sanitam successfully defended a suit filed by Rentokil seeking that the former be restrained from threatening, intimidating, harassing, embarassing and confusing Rentokil’s clients and customers over sanitary bins it provides.

Rentokil moved to the High Court after Sanitam wrote letters to the former’s clients warning them to stop using its sanitary bins, which Sanitam considered an infringement of its patent AP 773. Rentokil’s line of reasoning was that it had developed a new bin by changing certain features to distinguish it from Sanitam’s bin registered as AP 773. Therefore Rentokil claimed that by writing letters to its clients, Sanitam was seeking to enforce a patent over a completely different bin.

Sanitam’s defence was simply to focus on its granted patent and prove to the court that Rentokil’s bin was similar to its AP 773. To this end, Sanitam presented an expert report to substantiate that the two bins were similar and that the functionality of Rentokil’s bin was same as that covered under patent AP773.

It is argued that if Rentokil had focussed on Sanitam’s threatening letters rather the differences between its bins and Sanitam’s patent, Rentokil may have been successful with its application for injunction at the Industrial Property Tribunal under section 108 of the Industrial Property Act. This section reads:

“108. (1) Any person threatened with infringement proceedings who can prove that the acts performed or to be performed by him do not constitute infringement of the patent or the registered utility model or industrial design may request the Tribunal to grant an injunction to prohibit such threats and to award damages for financial loss resulting from the threats.”

All in all, this case is instructive to all litigants in industrial property matters to purse their matters with the Industrial Property Tribunal rather than with the High Court, in the first instance.

In Chemserve Cleaning Services Ltd v Sanitam Services EA Ltd [2009], the Industrial Property Tribunal ruled that it had no jurisdiction to hear applications to revoke patents granted by ARIPO. Sanitam challenged the Tribunal’s jurisdiction in a preliminary objection stating that section 59 of the Industrial Property Act only incorporates patents granted by ARIPO in relation to their effect in Kenya and that other issues such as revocation and not expressly contemplated in the section.

The section reads as follows:

“59. A patent, in respect of which Kenya is a designated state, granted by ARIPO by virtue of the ARIPO Protocol shall have the same effect in Kenya as a patent granted under this Act except where the Managing Director communicates to ARIPO, in respect of the application thereof, a decision in accordance with the provisions of the Protocol that if a patent is granted by ARIPO, that patent shall have no effect in Kenya.”

Therefore the main issue between the parties was the meaning of the word “effect” in the above section. Sanitam successfully convinced the Tribunal that “effect” simply means “the powers conferred to a right holder by the patent in Kenya”, therefore the only matters the Tribunal can hear related to infringement and compulsory licensing.

This decision by the Industrial Property Tribunal was reversed by the High Court in an ex parte judicial review application heard and determined by Justice Musinga on December 1, 2010. Chemserve Cleaning Services Ltd obtained an order to compel the Tribunal to reinstate, hear and determine an application for revocation of ARIPO patent AP 773 filed by Chemserve in 2008.

In Sanitam Services (EA) Ltd v Tamia Ltd Petition No. 305 of 2012, Sanitam sought reliefs from the court to have Tamia prevented from violating its IP rights over the invention patent no. AP773, including the destruction of all infringing bins in Tamia’s possession. Justice Majanja’s ruling sheds crucial light on the state’s obligations under the Constitution with regards to intellectual property rights under Articles 11 and 40.

The learned judge rightly dismissed Sanitam’s petition with two well-reasoned findings: firstly, the petitioner had failed to demonstrate how the State (in this case, KIPI and/or the Industrial Property Tribunal) had failed to honour its obligations under the Constitution. Secondly, it was unnecessary for the petitioner to invoke Article 22 of the Constitution to enforce IP rights since these are “ordinary rights” that can be enforced through the legal mechanisms provided by statute law (in this case the Industrial Property Act).

In Chemserve Cleaning Services Ltd v Sanitam Services EA Ltd [2013], the Industrial Property Tribunal rejected Chemserve’s request for the invalidation of Sanitam’s patent no AP 773.

This case is significant as the Tribunal makes several findings on the time period and burden of proof requirements when requesting revocation of a patent.

With regard to the time period requirement to revoke a patent, the Tribunal held that the legislative intent behind section 103 was to prevent a situation where a party becomes aware of a patent, then “literally sits on the right to revoke it until a later date for commercial convenience in the form of damages and accounts for profits”. The Tribunal also noted that Chemserve had failed to file for an extension of time under Rule 33 at the time it filed the request for revocation.

Even if Chemserve had filed its request in a timely manner, the Tribunal held that it had failed to meet the burden of proof required to establish that the patent was invalid. Chemserve argued that the patent lacked novelty and inventive step and formed part of prior art however it chose not to produce any evidence other than the affidavit and statement by its General Manager!

We are back full circle to 2014, where a recent report indicates that the Industrial Property Tribunal in a ruling made on 21 January 2014 has revoked patent no. AP 773. This blogger will examine this ruling once it is made available to the public.

All in all, it is beyond dispute that the long list of Sanitam cases presented above have in one way or another shaped the landscape of intellectual property litigation in Kenya and in Africa.