Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) and championing their utilisation in the Kenyan data protection environment

- Amrit Labhuram |

- October 5, 2021 |

- Cybersecurity,

- Data Protection,

- RIght to Privacy

What are PETs?

Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are a category of technologies capable of enabling, enhancing, and preserving data privacy concerns throughout the data lifecycle. They largely depend on the use of a data-centric approach for security and privacy.1 A data-centric approach to data security is focused on the information that needs protection instead of the network, device or application.2 Policymakers consider PETs as technical tools or methods for achieving compliance with data protection requirements or legislations. Generally, policymakers imply the functionality of PETs in unison with different organizational measures, including personnel management and access controls, audits, information security policies, and procedures.3

This nascent set of technologies, combined with changes in wider policy and business frameworks, could enable greater sharing and use of data in a privacy preserving, trustworthy manner. This could create new opportunities to use datasets without creating unacceptable risks. It also offers great potential to reshape the data economy, and to change, in particular, the trust relationships between citizens, governments and companies.4

Popular PETs and their Use cases

PETs can be broadly categorised as:5 tools that alter the data; tools that obscure data, by hiding or shielding data; and new systems and data architectures for processing, managing, and storing data with privacy in mind. Below are three examples of the new age PETs that are currently deployed, alongside their real-life applications:

-

Homomorphic encryption enables computational operations on encrypted data without decryption of that data.6 The original information (data in the clear, plaintext or cleartext data) is not revealed. The result of the computation is also encrypted, and needs to be decrypted (transformed back into plaintext) to see the results.7 Enveil, a PETs company, has partnered with DeliverFund, a counter-human trafficking intelligence organisation, to use homomorphic encryption based technology to provide access to a large human trafficking database in the US. Users of the platform will be able to cross-match and search on DeliverFund’s database without revealing the contents of their search or compromising the security of the data they are searching on.8

-

Differential privacy where data is anonymized via injecting noise (meaningless data) into the dataset studiously. It allows data experts to execute all possible (useful) statistical analysis without identifying any personal information.9 The goal of differential privacy is to add enough random, additional data so that real information is hidden amidst the noise.10 Differential privacy is better suited for larger databases due to the diminishing effect of a particular individual on a particular aggregate statistic alongside growth in the number of individuals in the database.11 In 2017, the US Census Bureau announced that it would be using differential privacy as the privacy protection mechanism for the 2020 decennial census. By incorporating formal privacy protection techniques, the Census Bureau will be able to publish a specific, higher number of tables of statistics with more granular information than previously.12

-

Secure Multi-party computation (SMPC) is a distributed computing system or technology capable of offering abilities for computing values of interest.13 SMPC takes input from multiple encrypted data sources without any party revealing private data to others.14 Therefore, SMPC has the potential to enable joint analysis on sensitive data held by several organisations.15 French-American startup, Owkin, is using Federated Learning to build a score that predicts the severity of a patient’s COVID-19 prognosis, and these scores support several hospitals in resource management and planning at the frontline.16

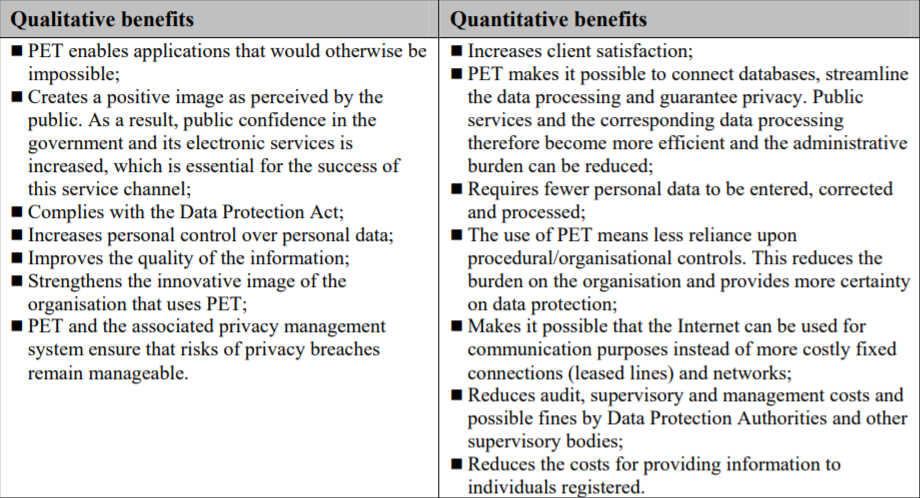

Benefits and Limitations of PETs

PETs, as discussed above, have various manifestations,benefits and limitations. The table below generally summarizes the qualitative and quantitative benefits that entities can expect to experience from the deployment of PETs.17

Despite the wide range of benefits that emanate from the use of PETs, there are various limitations that have prevented PETs from being a pragmatic solution to privacy concerns faced by data processing entities.

Universal limitations to the use of PETs can be surmised as the following:18

-

Lack of internal capacity and expertise within entities to deploy and manage complex PET solutions;

-

PETs are at varying stages of maturity and research. The variability in maturity and research adds to the complexity of PET adoption and makes it harder for firms to determine which PETs are appropriate and what resources they need to deploy; and

-

PETs do not automatically offer a complete guarantee that the entity deploying the tool or technique is in compliance with its data protection obligations. Enhanced PETs can be reversed or compromised, therefore PETs still need to be treated like any technical implementation, with oversight and management around use, access, and security

PETs and the Kenya Data Protection Act

The use of PETs by data processing entities in Kenya has the potential to enhance the utility of the data while simultaneously fulfilling the entities key data protection obligations. The Kenyan Data Protection Act (DPA) was enacted in November 2019 and is guided by the principles of data protection.19 Amongst the key obligations created is the responsibility for every data controller or data processor to implement data protection by design or by default. Privacy by design refers to the philosophy and approach of embedding privacy into the design specifications of various technologies, including the adoption and integration of privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs).20

The DPA offers entities discretion in determining the technical and organisational measures deployed by taking into consideration, amongst other factors, the cost of processing data and the technologies and tools used.21Under the DPA, this encompasses the use of appropriate technical and organisational measures which are designed to implement the data protection principles in an effective manner; and to integrate necessary safeguards for that purpose into the processing.22 This obligation is further reinforced by the draft Data Protection (General) Regulations which stipulates that a ‘data controller or data processor shall, throughout the lifecycle of processing of personal data, design technical and organizational measures to safeguard and implement the data protection principles’.23

Kenyan entities that possess the necessary resources to benefit from the application of PETs can utilise resources such as the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation – PETs adoption guide.24 The guide is primarily aimed at technical architects and product owners working on projects that involve the sharing or processing of sensitive information, and seeks to support decision-making around the use of PETs by helping the user explore which technologies could be beneficial to their use case.25

Conclusion

PETs are at the forefront of the revolution of how data driven organisations are conducting their business operations. The obligation to adopt and use privacy by design measures under the Kenyan DPA indicates the opportunity for Kenyan entities to select and implement PETs that are most suitable to meet their organisation’s policy objectives and targets.26

1 -<https://101blockchains.com/privacy-enhancing-technologies/>- on 13 September 2021.

2 -<https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2019/03/07/four-keys-to-data-centric-data-protection/?sh=52fa460d6455>- on 1 October 2021.

3 Ibid.

4 The Royal Society, Protecting privacy in practice- The current use, development and limits of Privacy Enhancing Technologies in data analysis, March 2019, Page 5 -<https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/privacy-enhancing-technologies/privacy-enhancing-technologies-report.pdf>- on 12 September 2021.

5 Asrow K and Samonas S, ‘Privacy Enhancing Technologies: Categories, Use Cases and Considerations’ Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June 2021, Page 4 -<https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/events/2021/august/bard-harstad-climate-economics-seminar/files/Privacy-Enhancing-Technologies-Categories-Use-Cases-and-Considerations.pdf> on 20 September 2021.

6 -<https://medium.com/golden-data/introduction-to-homomorphic-encryption-d903d02d4ce0>- on 17 September 2021.

7 Ibid.

8 -<https://cdeiuk.github.io/pets-adoption-guide/repository>- on 17 September 2021.

9 -<https://www.analyticssteps.com/blogs/what-differential-privacy-and-how-does-it-work>- on 17 September 2021.

10 Asrow K and Samonas S, ‘Privacy Enhancing Technologies: Categories, Use Cases and Considerations’ Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June 2021, Page 10 -<https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/events/2021/august/bard-harstad-climate-economics-seminar/files/Privacy-Enhancing-Technologies-Categories-Use-Cases-and-Considerations.pdf>- on 18 September 2021.

11 -<https://101blockchains.com/top-privacy-enhancing-technologies/>- on 17 September 2021.

12 The Royal Society, Protecting privacy in practice- The current use, development and limits of Privacy Enhancing Technologies in data analysis, March 2019, Page 45 -<https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/privacy-enhancing-technologies/privacy-enhancing-technologies-report.pdf> on 20 September 2021.

13 -<https://101blockchains.com/top-privacy-enhancing-technologies/>- on 17 September 2021.

14 Ibid.

15 The Royal Society, Protecting privacy in practice- The current use, development and limits of Privacy Enhancing Technologies in data analysis, March 2019, Page 9

-<https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/privacy-enhancing-technologies/privacy-enhancing-technologies-report.pdf>- on 18 September 2021.

16 -<https://cdeiuk.github.io/pets-adoption-guide/repository>- on 20 September 2021.

17 Koorn R, Gils H, Hart J, Overbeek P and Tellegen R, ‘Privacy-Enhancing Technologies White Paper for Decision-Makers’ Directorate of Public Sector Innovation and Information Policy, December 2004, Page 39 -<https://is.muni.cz/el/1433/podzim2005/PV080/um/PrivacyEnhancingTechnologies_KPMGstudy.pdf>- on 20 September 2021.

18 Asrow K and Samonas S, ‘Privacy Enhancing Technologies: Categories, Use Cases and Considerations’ Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June 2021, Page 5 -<https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/events/2021/august/bard-harstad-climate-economics-seminar/files/Privacy-Enhancing-Technologies-Categories-Use-Cases-and-Considerations.pdf>- on 20 September 2021.

19 Section 25, Data Protection Act, (Act No. 24 of 2019). Key principles include: Processing in accordance with the right to privacy; Lawful, fair and transparent processing; Purpose limitation, Data minimization; Storage limitation; Data accuracy etc.

20 -<https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/standards/ict-and-communication/data/pbd-privacy-design_en.html>- on 17 September 2021.

21 Section 41(3)(e), Data Protection Act, (Act No. 24 of 2019).

22 Section 41(1), Data Protection Act, (Act No. 24 of 2019).

23 Regulation 26(b), Data Protection (General) Regulations, 2021.

24 -<https://cdeiuk.github.io/pets-adoption-guide/adoption-guide>- on 20 September 2021.

25 Ibid.

26 Koorn R, Gils H, Hart J, Overbeek P and Tellegen R, ‘Privacy-Enhancing Technologies White Paper for Decision-Makers’ Directorate of Public Sector Innovation and Information Policy, December 2004, Page 44

-<https://is.muni.cz/el/1433/podzim2005/PV080/um/PrivacyEnhancingTechnologies_KPMGstudy.pdf>- on 20 September 2021.