Recap: Day 2 of JKUAT Conference on Protection of Intellectual Property Rights

- Victor Nzomo |

- July 14, 2017 |

- CIPIT Insights,

- Intellectual Property

Editor’s Note: For a recap of Day 1, please see here.

The final day of the #JKUATLawIP conference was kicked off by Shirley Genga, a law lecturer at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), who spoke on protecting intellectual property rights in big data with a focus on Kenya. Genga noted that in the absence of any formal legal regime for big data, the existing laws of contract as well as copyright protection will have to suffice. For a discussion of the question of IP and database rights protection, please see this blogger’s post here. Next up was James Tugee from Hamilton, Harrison & Mathews, Advocates who made a case for legislation of the right to publicity in Kenya.

In Tugee’s considered view, a stand-alone law on publicity rights would make image rights easier to enforce and promote certainty on allowed and restricted uses of one’s image. Tugee’s seemingly pro-celebrity stance was rooted in Lockean labour theory which he highlighted in his presentation and justified the need for this image rights legislation as a means to ensure that Kenyan public figures such as athletes, musicians and socialites are not deprived of compensation from the commercial use of their likeness. For a thorough discussion of the rise of image rights claims in Kenya, please see this blogger’s articles here and here. Next up was Henry Mutai, a long-time friend of CIPIT and former head of Kenya Industrial Property Institute (KIPI) spoke on the challenges of geographical indication (GI) protection in Kenya using the example of the BASMATI case which he made a ruling on as the then Registrar of Trade Marks at KIPI. Mutai concludes that the framework in section 40A of the Trade Marks Act is not sufficient to protect GIs.

The highlight of the first session of the morning was an interesting presentation by the young-at-heart mechanical engineering don at JKUAT, Benson Kariuki (pictured above) who shared his journey at the helm of JKUAT’s Directorate of Intellectual Property Management and University Industry Liaison (DIPUIL). Kariuki confessed that he had little formal knowledge of intellectual property (IP) prior to his involvement with DIPUIL and even less interest in managing JKUAT’s IP matters at the onset. Nonetheless, Kariuki took on his assignment at DIPUIL and gradually learnt the ins and outs of the IP system, thanks to training offered by World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Academy and training support received from KIPI during Mutai’s tenure as Managing Director. In terms of hierarchical structure, Kariuki noted that DIPUIL could have either been within either the Research Office or the Legal Office but instead it ended up under the office of the VC at JKUAT. According to Kariuki, this positioning is advantageous to DIPUIL because there is direct access to the CEO of the institution with little or no bureaucracy. Under Kariuki’s leadership, JKUAT successfully poached Fred Otswong’o, a senior patent agent (and former KIPI patent examiner) to run JKUAT patent drafting office. Currently, JKUAT’s IP portfolio boasts five (5) granted patents and utility models with thirty eight (38) patent and utility model applications pending as well as eight (8) trademarks (half of which are in use), two (2) copyright registrations and one (1) industrial design.

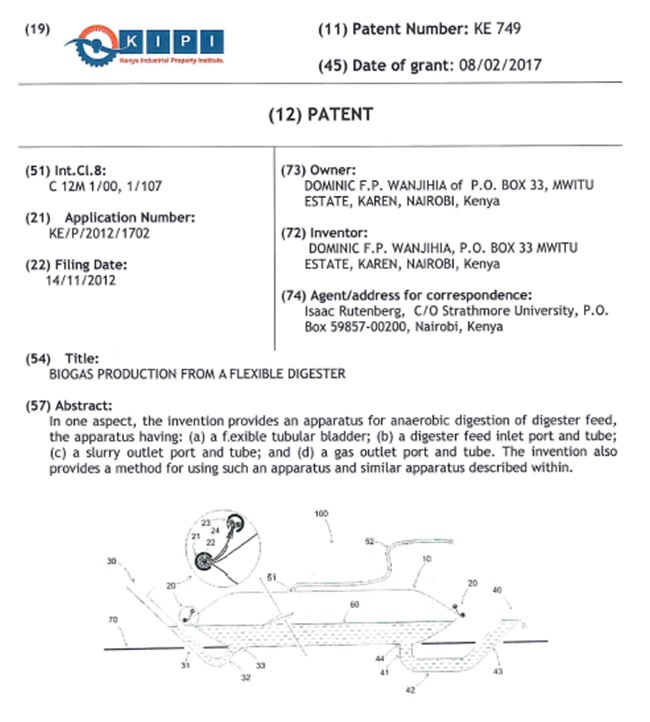

In the panel of the second session of the morning, the scientists outnumbered the lawyers. Leading the pack was Dr. Rutenberg, a trained chemist and legal practitioner, who captivated the conference with his presentation on the patenting process in Kenya using the example of the patent application pictured above. Rutenberg discussed several key milestones in the patenting process namely, the filing date, the formalities report, substantive examination report, substantive response, notice allowance and date of grant. From start to finish, the patent process for the application in question took five (5) years which according to Rutenberg is not unusual even in developed countries. One of the key take-aways from Rutenberg’s presentation was that CIPIT’s doors are open to both scientists and lawyers interested in becoming patent experts. For IP practitioners, the CIPIT website (www.cipit.org) contains a wealth of information and data ranging from a fully searchable database for patents as well as trademarks, a database of IP case law, videos on patent drafting, resources from our various IP and IT projects and of course, there’s a link to this blog!

Other speakers during the session included Florence Mwangangi of Law Society of Kenya (LSK) in charge of the ICT & IP Committee of LSK who presented on software protection through IP rights. Mwangangi mentioned that the LSK Committee is keen on devolving IP awareness and capacity building to the counties as evidenced by their recent visit to Kajiado County. Sylvance Sange, MD of KIPI and Mutai’s successor, gave an overview of the industrial property system in Kenya focusing on the state of implementation of KIPI’s current Strategic Plan which lapses mid next year. Sange revealed that KIPI would be relocating its headquarters in Nairobi from South C to Waiyaki Way, opposite the Communications Authority of Kenya. Sange also reported that the digitisation of KIPI patent registry was complete and that of the trade marks registry was almost done, after which some information would be made available to the public. Fred Otswong’o spoke candidly about the challenges of patent drafting in universities including patent prosecution before KIPI, where he had previously served for well over a decade. In his remarks, Otswong’o urged the government (including KIPI) to re-introduce novelty searches for applications for utility model certificates (UMCs) for the benefit of Kenya’s innovative ecosystem. In this regard, CIPIT has argued for a return to substantive examination of UMCs in a recent article published in the African Journal of Information and Communication available here.

Eng. B.K. Kariuki

Fred Otswong'o

John Hadullo