The Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure in Kenya

- Victor Nzomo |

- October 1, 2017 |

- CIPIT Insights,

- Patent

The focus of this blogpost is on the some of the issues arising around the Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for the Purposes of Patent Procedure. As many may know, the Budapest Treaty was concluded in 1977 and has been open to States party to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (1883). As at 2017, 80 States were party to the Treaty. Interestingly, there are only three African countries that have signed the Treaty, namely Tunisia, Morocco and South Africa.

As many may know, the Treaty was intended to aid in disclosure requirement under patent law where the invention involves a microorganism or the use of a microorganism. Such inventions relate primarily to the food and pharmaceutical fields. Since such disclosure is not possible in writing, it can only be effected by the deposit, with a specialized institution, of a sample of the microorganism.

It is in order to eliminate the need to deposit in each country in which protection is sought, that the Treaty provides that the deposit of a microorganism with any “international depositary authority” suffices for the purposes of patent procedure before the national patent offices of all of the contracting States and before any regional patent office (if such a regional office declares that it recognizes the effects of the Treaty). The European Patent Office (EPO), the Eurasian Patent Organization (EAPO) and the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO) have made such declarations.

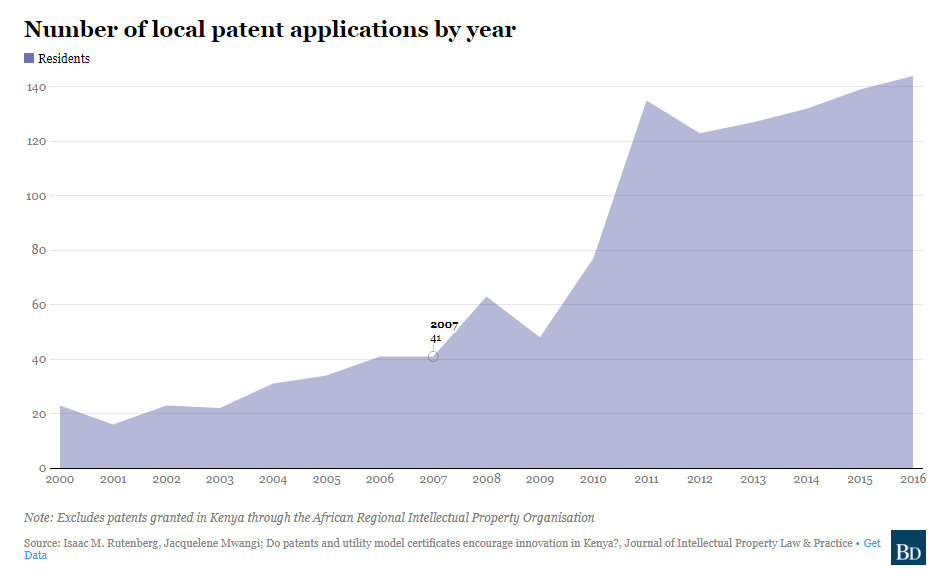

With that background in mind, this blogger suspects that most African states

may not be ready to implement a Treaty such as the Budapest Treaty at present. Taking the Kenyan scenario for instance, local patent applications are very few and whilst Kenya may have no problem with the Treaty per se, it would be a cumbersome, expensive venture. For the foreseeable future, the real beneficiaries of the system under Budapest Treaty would be the developed countries since they remain ardent users of the patent system. Judging from the 3 countries that are signatories to the treaty, it is clear that capacity is a big impediment.

To highlight this issue of capacity, let us consider the “international depositary authority” provision under the Treaty. What the Treaty calls an “international depositary authority” is a scientific institution – typically a “culture collection” – which is capable of storing microorganisms. Such an institution acquires the status of “international depositary authority” through the furnishing by the contracting State in the territory of which it is located of assurances to the Director General of WIPO to the effect that the said institution complies and will continue to comply with certain requirements of the Treaty.

In this connection, it is important to note that there is no institution in Africa that has been recognised under the Treaty as a “international depositary authority” whereas they are currently 42 such authorities in other countries worldwide including: seven in the United Kingdom, three in the Russian Federation, in the Republic of Korea, and in the United States of America, two each in Australia, China, India, Italy, Japan, Poland, and in Spain, and one each in Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, the Netherlands and Slovakia.

Initially Kenya proposed to sign the Treaty and had identified two depositaries i.e Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (KARI) however the main challenge seemed to be a lack of capacity in proper handling of the samples and the means to maintain the cultures or strains to the required standards. Not to mention the increased costs and logistics involved in the coordination between the IP office and the depositaries.